|

|

How does technology shape how we know?

Does technology aid or hinder cognition?

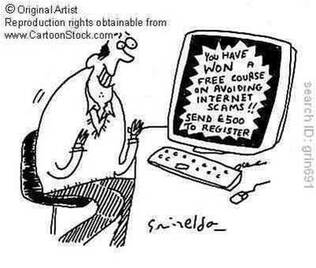

You only need to be browsing the Internet for a few minutes before you come across a wealth of knowledge claims. On the one hand, it fantastic that we have so much information at our disposal. When I was your age and I needed some information for a history project, it took me a lot of time to get what I wanted. I had to physically cycle to the town library, research the index box, find the historical journal I needed, copy the details I needed by hand, and then cycle back home. Now, it takes a few seconds to "Google" the same information. On the other hand, the very same wealth of information and knowledge that we have at our disposal, can be overwhelming. After all, how do we select the best and most reliable sources? How do we know what we should believe? It can indeed be difficult to distinguish between genuine, well founded knowledge and well presented but unfounded claims.

The internet enables us to come across a staggering amount of (sometimes contradictory) knowledge.

But how do we know what is true? How do we know what we should believe?

But how do we know what is true? How do we know what we should believe?

|

|

Reflection: Are there ethical limits to the progress in knowledge acquired through the use of technology?

Lesson idea: Deepfakes

Learning activity:

Read the article below about Deepfakes. Then discuss in groups:

How has access to technology and multimedia impacted the way in which we can rely on our sense to acquire knowledge?

Read the article below about Deepfakes. Then discuss in groups:

How has access to technology and multimedia impacted the way in which we can rely on our sense to acquire knowledge?

FOR FUN: Create your own deepfake video.

This link looks good (but it is not for free). Other apps are available online too.

Let's think:

How does this experience of creating a Deepfake change your view on the age-old saying "seeing is believing"?

|

|

Do you only know what you want to know?

Filter bubbles:

.A situation in which an Internet user encounters only information and opinions that conform to and reinforce their own beliefs, caused by algorithms that personalize an individual’s online experience.

‘the personalization of the web could gradually isolate individual users into their own filter bubbles’.

Oxford Dictionary

In this digital information age, can we still speak of things such as fact and truth?

The advancements in technology have enabled us to gain access to a much wider range of knowledge. In a way, knowledge has also become more "democratic". Almost anyone can access, and even disseminate, knowledge online. At first sight, this seems wonderful, because we may feel that the quality of knowledge could be improved if a large community is able to share and evaluate it. Nevertheless, technology can also hinder our search for knowledge. If technology allows virtually anyone to express and propagate (what seems to be) knowledge, we are bound to come across some less reliable sources and even unfounded claims. Unfortunately, not everyone assesses those claims when they stumble across them. The current political climate in many countries, for example, shows that large groups of people can easily be swayed by emotionally appealing but essentially false claims. We could argue that mere "belief" or "emotional" appeal has always be a decisive factor in what we tend to accept as knowledge. The popularity of (ancient) religious knowledge claims about the state of the natural world (eg intelligent design), for example, arguably illustrates this. Some people are easily swayed by emotionally appealing claims rather than those that appeal to reason, fact and veracity.

When it comes to politics, we should have a closer look at the concept of "post-truth". Nowadays, the way in which an argument is presented seems to somehow weigh more heavily than the actual content of the argument. Rhetoric is obviously not new. However, the way in which we currently engage with what could be considered to be fact or truth is quite unusual. This "disinterested engagement" with the truth can partly be explained through the way in which information technology shapes cognition. The overwhelming amount of information at our disposal makes it more difficult to determine what is true knowledge. This may lead us to accept emotionally appealing rather than factually correct claims. We find ourselves in contradictory times. On the one hand, we have more knowledge at our disposal than ever before. On the other hand, we don't know what to do with all this knowledge. When we don't know how to distinguish between good and bad knowledge, many of us choose the easiest or most appealing claims over the most accurate ones. And this does not always make us more knowledgeable...

When it comes to politics, we should have a closer look at the concept of "post-truth". Nowadays, the way in which an argument is presented seems to somehow weigh more heavily than the actual content of the argument. Rhetoric is obviously not new. However, the way in which we currently engage with what could be considered to be fact or truth is quite unusual. This "disinterested engagement" with the truth can partly be explained through the way in which information technology shapes cognition. The overwhelming amount of information at our disposal makes it more difficult to determine what is true knowledge. This may lead us to accept emotionally appealing rather than factually correct claims. We find ourselves in contradictory times. On the one hand, we have more knowledge at our disposal than ever before. On the other hand, we don't know what to do with all this knowledge. When we don't know how to distinguish between good and bad knowledge, many of us choose the easiest or most appealing claims over the most accurate ones. And this does not always make us more knowledgeable...

|

|

Does technology help or hinder the equal access to knowledge?

Reflection:

How might technology exacerbate or mitigate unequal access, and divides in our access, to knowledge?

How might technology exacerbate or mitigate unequal access, and divides in our access, to knowledge?

As seen previously, technology seems to enable the democratisation of knowledge. Knowledge is easily accessible. Less educated, non-expert and non-elite groups of people can now find knowledge and information that was previously only available to the few. However, technology can be used to deliberately misinform large groups of people. Technology can be used to gather data about your (online) behaviour. This data can be used by powerful and elitist entities. Companies can use data to advertise products and shape your purchasing behaviours. In some instances, technology has even been used to sway voters' opinion. In his sense, we may wonder whether technology has hampered rather than enabled the equal access to knowledge. How could we use technology responsibly to enable progress within knowledge production, the fair distribution of knowledge and a sustained respect for human rights such as freedom and privacy?

"The social dilemma" explores the role of social media in manipulating our access to knowledge and shaping what we consider to be true.

|

|

|

|

|

How does the impact of technology on knowledge give rise to new ethical debates?

As seen previously, technology can both drive and hinder the equal access to knowledge. In addition to ethical questions regarding fair and equal access to knowledge, new technology has given rise to other important moral discussions. Some of these relate to data gathering and the notion of objectivity. Others touch upon individual freedom and the use of algorithms to describe human behaviour. Technology is sometimes used to understand human behaviour or to gather data on human behaviour. On the one hand, this may seem harmless and even useful, because it seems to remove a great deal of human bias. For example, if an AI "calculates", describes and predicts behavioural traits, it may be better at this job than a human being. After all, AI systems are fast and can process a much wider range of data than a human researcher. However, technology may give us the illusion of objectivity. Once the original human input is no longer visible, we tend to forget that it was once there.

Computers may be better and faster at spotting patterns than human beings, but how do they get access to their wide range of data? Many of us are unaware that our personal data is continually being collected when we leave a digital footprint. What kind of data is being collected? What methods are used to get this data? Does this data give the full picture of what you are really like as a human being? All this raises many ethical questions.

In addition, you should remember that the kind of knowledge produced by technology it is not always ethical in terms of nature or purpose. Because this field is so new and different countries may have different legal regulations, unethical knowledge (or knowledge that can be used for unethical purposes) seems to creep in. For example, current face recognition technology proposes that it can say whether someone is gay or straight by looking at someone's photo. Regardless of whether this knowledge is true or not, we should question how the proposed knowledge of such algorithms could be used. Systems that claim they can describe and predict human behaviour through face recognition could potentially lead to discrimination. So how do we ethically define the limits of progress in knowledge that has been created with the help of technology?

The advancements of knowledge through technology come with renewed ethical debates. What are the ethical limits to progress of knowledge created through technology? How much data should information systems be allowed to possess about us? Who possesses knowledge that originates from technology? Sometimes, we have to program machines that are required to take ethical decisions, such as driverless cars. Interestingly, these machines will take decisions without resorting to emotion, as opposed to humans. So, what criteria should we use as foundations for our ethical programming of these machines? Is the absence of emotion an improvement on ethical decisions of machines (as opposed to humans) or not? What do we do when two principles contradict themselves? Is it even possible to come up with a universally satisfactory list of criteria?

Computers may be better and faster at spotting patterns than human beings, but how do they get access to their wide range of data? Many of us are unaware that our personal data is continually being collected when we leave a digital footprint. What kind of data is being collected? What methods are used to get this data? Does this data give the full picture of what you are really like as a human being? All this raises many ethical questions.

In addition, you should remember that the kind of knowledge produced by technology it is not always ethical in terms of nature or purpose. Because this field is so new and different countries may have different legal regulations, unethical knowledge (or knowledge that can be used for unethical purposes) seems to creep in. For example, current face recognition technology proposes that it can say whether someone is gay or straight by looking at someone's photo. Regardless of whether this knowledge is true or not, we should question how the proposed knowledge of such algorithms could be used. Systems that claim they can describe and predict human behaviour through face recognition could potentially lead to discrimination. So how do we ethically define the limits of progress in knowledge that has been created with the help of technology?

The advancements of knowledge through technology come with renewed ethical debates. What are the ethical limits to progress of knowledge created through technology? How much data should information systems be allowed to possess about us? Who possesses knowledge that originates from technology? Sometimes, we have to program machines that are required to take ethical decisions, such as driverless cars. Interestingly, these machines will take decisions without resorting to emotion, as opposed to humans. So, what criteria should we use as foundations for our ethical programming of these machines? Is the absence of emotion an improvement on ethical decisions of machines (as opposed to humans) or not? What do we do when two principles contradict themselves? Is it even possible to come up with a universally satisfactory list of criteria?

|

|

Reflection: How does the medium used change the way that knowledge is produced, shared or understood?

Lesson idea: How does the medium used affect how we know?

On methods&tools, knowledge and technology.

TASK:

- Give students (who work in groups) something they need to pursue knowledge about (eg a partical aspect of the natural world).

- Allocate each group of students a different medium they could use to produce, share or understand this topic.

- Students research what they could know about their given topic, having the allocated medium at their disposal.

- Students research the advantages of their allocated medium, but also the possible pitfalls (for production/sharing/understanding knowledge).

- Discussion of the impact of a medium on the production, sharing and understanding of knowledge

Follow-up research: Consider the historical development of knowledge within an IBDP subject and the role technology has had within this development. Focus both on the acquisition and the distribution/understanding of knowledge.

Let's think: What if?

What if certain technology had not been available throughout this historical development?

Would that affect how we know within this subject?

What might we know in the future, given continued technological development?

Are there (or should there be) limits to the possibilities of technology in terms of knowledge production and acquisition?

|

|

How not to drown in the sea of knowledge?

I mentioned previously that some people might find it overwhelming to have so much knowledge at their disposal. A few generations ago, titles of (history) textbooks rarely hinted at the least possibility of doubt. The definite article "the" in "The Building of our nation" (see image left), suggests that it is possible to present an accurate and complete history of an entire nation in less than 500 pages. It also suggests that you should not look further to get other perspectives. Many people feel comfortable with this kind of knowledge. In the past, your teachers told the truth, you had to learn this truth by heart and reproduce it elsewhere (on an exam paper). This represented your possession of knowledge. However, throughout post-modern times (1980's-1990's), we started to question these absolute truths. We understood that single stories could be dangerous and approached "truth" with scepticism and even relativism. Post-modern ideas proposed that we should include a wider range of perspectives, including those of the non-elite and less powerful groups. This idea was very attractive at the time because it led to tolerance and and a greater inclusion of a wealth of ideas. Moving on a few years, came the age of information technology. In addition to our changed post-modern mindset, we also had the Internet at our disposal. With the advent of the Internet came the access to information on a scale that was unheard of before. Initially, this meant that we could find information and even knowledge in a matter of seconds. Increasingly, this also means that anyone could share knowledge and reach audiences you would never have reached previously. Nowadays, anyone can become a Youtuber, anyone can contribute to Wikipedia, and anyone can create a website. In sum, knowledge has become more democratic in two ways: virtually anyone can access it and virtually anyone can create it. On the one hand, this is great. Knowledge has become much less a thing of the elite or the entitled. It is much easier to find knowledge, it feels like we know more. However, with all this information at our disposal, how do we distinguish between "good" and "bad" knowledge, "reliable" and "unreliable" sources?

This is not easy. Perhaps not unsurprisingly, many people have given up on this quest. Instead, they do not only think that it is impossible to say something with certainty (they refute the notion of facts); they also feel that facts have become somewhat irrelevant. In politics, this phenomenon is called the post-truth: "Relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief." (Oxford Dictionary). Although it is very important to be wary of people who claim to have found "the truth" (this can lead to dogma), we should equally be wary of people who claim that the truth does not matter. When we pretend that facts don't exist, or present obvious knowledge as "fake" news, we create room for our own agenda, propaganda and emotionally appealing but morally incorrect politics. Some politicians take advantage of this situation. ‘In this era of post-truth politics, it's easy to cherry-pick data and come to whatever conclusion you desire’ Oxford Dictionary).

So, what does this mean for you? Within TOK lessons, you will learn to critically assess your sources, ask questions about the reliability of knowledge claims and filter the data at your disposal. Technology has allowed us to access a wealth of knowledge, but this can be difficult. We hope you will not assume that facts don't exist anymore. They do. But you should question what counts as a fact, under what circumstances you could accept expert opinion and how technology has impacted how we filter data and information. You should learn to filter your news and question what you can believe. You should evaluate the methods you use to do so. In short, you should learn to swim rather than drown in the sea of "knowledge" surrounding us.

This is not easy. Perhaps not unsurprisingly, many people have given up on this quest. Instead, they do not only think that it is impossible to say something with certainty (they refute the notion of facts); they also feel that facts have become somewhat irrelevant. In politics, this phenomenon is called the post-truth: "Relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief." (Oxford Dictionary). Although it is very important to be wary of people who claim to have found "the truth" (this can lead to dogma), we should equally be wary of people who claim that the truth does not matter. When we pretend that facts don't exist, or present obvious knowledge as "fake" news, we create room for our own agenda, propaganda and emotionally appealing but morally incorrect politics. Some politicians take advantage of this situation. ‘In this era of post-truth politics, it's easy to cherry-pick data and come to whatever conclusion you desire’ Oxford Dictionary).

So, what does this mean for you? Within TOK lessons, you will learn to critically assess your sources, ask questions about the reliability of knowledge claims and filter the data at your disposal. Technology has allowed us to access a wealth of knowledge, but this can be difficult. We hope you will not assume that facts don't exist anymore. They do. But you should question what counts as a fact, under what circumstances you could accept expert opinion and how technology has impacted how we filter data and information. You should learn to filter your news and question what you can believe. You should evaluate the methods you use to do so. In short, you should learn to swim rather than drown in the sea of "knowledge" surrounding us.

|

|

How should we engage with knowledge from the Internet?

Reflection: To what extent is the internet changing what it means to know something?

By studying the optional theme of knowledge and technology you are encouraged to become that bit less gullible when you come across online knowledge. You will learn not to take everything you hear face value. We should stop deluding ourselves by choosing our most convenient truth. In order to distinguish between fact and fiction in our search for knowledge, it is invaluable to analyse ourselves as a knower. It is important to evaluate how we deal with information that we come across online and how we share knowledge. We should examine the validity of knowledge claims and their justifications, rather than just debunking them without being able to justify our points of view.

|

|

Technology and cognition

Reflection: To what extent are technologies such as the microscope and telescope merely extensions to the human senses or do they introduce radically new ways of seeing the world?

As seen before, technology has allowed for the dissemination of knowledge at a much faster rate than was previously imaginable. However, technology has also affected the way in which we gather knowledge. Technology such as telescopes and microscopes have made it possible to enhance human sense perception. These tools allow us to perceive what is beyond the capacities of our human frame. Thanks to technology we now have sensory proof for scientific theories that could not have been proven without it. For example, technology allowed us to detect the sound of gravitational waves. This is a big deal, because technology allowed scientists to confirm the second part of Einstein's publication of the general theory of relativity, i.e. gravitational waves, about 100 years after his initial predictions. And, more recently, a network of eight telescopes across the world, allowed us to release the very first image of a black hole, located 500 million trillion km away.

Technology has pushed the boundaries of human sense perception. It can even be argued that it has created an entirely different lens through which we can see the world. To some extent, technology has radically transformed (human) cognition. The advent of A.I and recent developments in machine learning may even make us question whether knowledge could reside outside human cognition.

Technology has pushed the boundaries of human sense perception. It can even be argued that it has created an entirely different lens through which we can see the world. To some extent, technology has radically transformed (human) cognition. The advent of A.I and recent developments in machine learning may even make us question whether knowledge could reside outside human cognition.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Knowledge and AI

These are exciting times. Every week or so, you hear about a new major feat of an AI that achieved something that we previously considered impossible. Not only can machines spot patterns at amazing rates, they can also output things that surprise us and, in some case, even learn new things. Machine learning is truly fascinating and it pushes the boundaries of how we understand concepts such knowledge. Admittedly, as human beings we are generally better than machines at the use of creative imagination and the skills to deal with the unexpected. Unlike machines, humans are also pretty good at generalising and recognising something we have never seen before. However, recent technological developments show that new progress in machine learning is possible, even in this area. At MIT, researchers merged symbolic and statistical AI to teach machines to reason about what they see. In fact, we have seen AI create original art, beat humans at a chess game, deliver a medical diagnosis and discover the proof for mathematical theorems. Modern machines can also learn things with minimal human input. So what does all this imply? What does this mean for knowledge? Should we redefine our "human" concept of knowledge? Can a machine ever "know" something? Or can it merely create knowledge? How important is the human belief in knowledge for it to be considered knowledge?

|

|

|

|

|

Technology plays an important role within the dissemination of knowledge. In addition, recent technological developments have enabled us to create knowledge that we would not have been able to create without it. Technology can also help us reach evidence that would have been unobtainable without it. Although technology and computer programs are initially created by humans, some machines have actually managed to create new knowledge without human intervention. Artificial Intelligence is becoming more and more impressive each day. This leads us to discuss whether human beings are needed to create new knowledge, whether machines can learn, or think autonomously. We may even question whether machines can "know" and whether a "knower" is necessarily human.

Possible knowledge questions about knowledge and technology

Acknowledgement: these knowledge questions are taken from the official IBO TOK Guide, (2022 specification).

|

Scope

Ethics

|

Methods and Tools

Perspectives

|

Making connections to the core theme, as suggested by the TOK Guide

- How might personal prejudices, biases and inequality become “coded into” software systems?

- How does technology extend and modify the capabilities of our senses?

- What moral obligations to act or not act do we have if our knowledge is tentative, incomplete or uncertain?