True wisdom is less presuming than folly. The wise man doubteth often, and changeth his mind; the fool is obstinate, and doubteth not; he knoweth all things but his own ignorance." Akhenaton

|

|

Introduction

Reflection: What kind of things would you probably have accepted as knowledge if you had been born 500 years ago?

What would you, most likely, have rejected?

What does this imply?

In Theory of Knowledge classes, you have to study one compulsory core theme and two optional themes. The themes are primarily assessed through the TOK exhibition, in which you will demonstrate how TOK manifests itself in the real world. Throughout the lessons on the core theme, you will explore what it means to know and what knowledge is. You will examine the factors that shape how you make sense of the world. You will also discover where your values come from and what shapes your perspectives. In addition, you will reflect on how you engage with knowledge around you. In this respect, it is important to acknowledge that the communities you belong to play an important role within how you construct, share and evaluate knowledge.

As a thought experiment, you could ask yourself whether you would accept, let's say, the Theory of Evolution if you had been born 500 years ago, or currently lived in a remote mountain village the other side of the world. Alternatively, you could wonder how you would have engaged with the #MeToo movement be if you had grown up in a community with very different (religious) values, or if you were of "the other" gender (if we can speak in binary oppositions, that is)? Or, ...what would the international education system look like if you, your teachers and the IB community as a whole, primarily communicated in Swahili?

What you accept as knowledge may well depend on your perspective, language, values and the community of "knowers" you are most familiar with. You may well possess assumptions and even bias you were previously unaware of.

By exploring the core theme, you will hopefully learn to think more carefully about the validity of knowledge and avoid accepting things face value. Unfortunately, people can be manipulated and deliberately misinformed to serve political, religious, idealist or economic agendas. Powerful people and entities might use unreliable sources and dubious research to present things as good quality knowledge or even fact. For example, it seems obvious that medical research into the effects of tobacco (albeit indirectly) sponsored by a tobacco company is less likely to be trustworthy. However, in reality, these kinds of practices occur more often than you think. It is important to check your sources and to fact-check claims about knowledge you come across.

In theory, the current availability of (digital) technology should allow us to "fact-check" more easily. In addition, our current access to vast amounts of information should, arguably, make us more knowledgeable than "the average medieval Joe". However, with the expansion of (social) media, false information and erroneous knowledge claims can spread incredibly fast whilst reaching large amounts of people. When we are confronted with such information, we do not always check our sources. The "visible" nature of this information can exacerbate the situation, because we place (too) much trust on what we can perceive through our senses. The current phenomenon of "deepfakes", for example, illustrates (in an albeit extreme way) that "seeing is no longer believing". Technology allows us to manipulate images and videos, select "convenient" information (whilst leaving out the rest) and quickly find some "evidence" (from bad sources) to support silly claims.

By evaluating wrong and potential harmful knowledge claims, you may become wiser, more knowledgeable and even more tolerant and open-minded. We should avoid dogma and learn to distinguish between valid and invalid arguments, reliable and unreliable sources and facts or non-facts. However, it is equally important to steer clear of relativism. Let us hope that we do not end up in a world where facts do not matter anymore. You should not dismiss the blatantly obvious as "fake news" simply because it does not suit your agenda, or use concepts such as "alternative facts" to avoid blame for what you have done. This can be equally dangerous and manipulative. When we are confronted with a wealth of evidence that shows the earth is round, it would be foolish to claim that it is flat because this suits your intuition better. Likewise, when it is beyond reasonable doubt that climate change is happening, you could question the sincerity of people who brush this fact off as "fake news".

As a thought experiment, you could ask yourself whether you would accept, let's say, the Theory of Evolution if you had been born 500 years ago, or currently lived in a remote mountain village the other side of the world. Alternatively, you could wonder how you would have engaged with the #MeToo movement be if you had grown up in a community with very different (religious) values, or if you were of "the other" gender (if we can speak in binary oppositions, that is)? Or, ...what would the international education system look like if you, your teachers and the IB community as a whole, primarily communicated in Swahili?

What you accept as knowledge may well depend on your perspective, language, values and the community of "knowers" you are most familiar with. You may well possess assumptions and even bias you were previously unaware of.

By exploring the core theme, you will hopefully learn to think more carefully about the validity of knowledge and avoid accepting things face value. Unfortunately, people can be manipulated and deliberately misinformed to serve political, religious, idealist or economic agendas. Powerful people and entities might use unreliable sources and dubious research to present things as good quality knowledge or even fact. For example, it seems obvious that medical research into the effects of tobacco (albeit indirectly) sponsored by a tobacco company is less likely to be trustworthy. However, in reality, these kinds of practices occur more often than you think. It is important to check your sources and to fact-check claims about knowledge you come across.

In theory, the current availability of (digital) technology should allow us to "fact-check" more easily. In addition, our current access to vast amounts of information should, arguably, make us more knowledgeable than "the average medieval Joe". However, with the expansion of (social) media, false information and erroneous knowledge claims can spread incredibly fast whilst reaching large amounts of people. When we are confronted with such information, we do not always check our sources. The "visible" nature of this information can exacerbate the situation, because we place (too) much trust on what we can perceive through our senses. The current phenomenon of "deepfakes", for example, illustrates (in an albeit extreme way) that "seeing is no longer believing". Technology allows us to manipulate images and videos, select "convenient" information (whilst leaving out the rest) and quickly find some "evidence" (from bad sources) to support silly claims.

By evaluating wrong and potential harmful knowledge claims, you may become wiser, more knowledgeable and even more tolerant and open-minded. We should avoid dogma and learn to distinguish between valid and invalid arguments, reliable and unreliable sources and facts or non-facts. However, it is equally important to steer clear of relativism. Let us hope that we do not end up in a world where facts do not matter anymore. You should not dismiss the blatantly obvious as "fake news" simply because it does not suit your agenda, or use concepts such as "alternative facts" to avoid blame for what you have done. This can be equally dangerous and manipulative. When we are confronted with a wealth of evidence that shows the earth is round, it would be foolish to claim that it is flat because this suits your intuition better. Likewise, when it is beyond reasonable doubt that climate change is happening, you could question the sincerity of people who brush this fact off as "fake news".

|

|

What does it mean to know?

Activity: How do you translate "to know" or "knowledge" into other language(s) you speak/learn?

Which aspects of "knowing" or "knowledge" do these translations highlight?

What does this imply?

Theory of Knowledge classes centre around the question 'How do we know what we know?'. In TOK you are invited to wonder and wander, to reflect upon knowledge you have gathered throughout the years and to analyse yourself as a knower. Throughout your exploration of the core theme, you will explore knowledge questions on the four elements of the TOK course: scope, perspectives, methods and tools and ethics. The whole course will be interspersed with such questions about knowledge.

| epistemology.pdf | |

| File Size: | 321 kb |

| File Type: | |

|

|

Let's start our journey with a couple of questions:

What community/ies of knowers do you belong to?

How has your culture, upbringing, gender, point of time in which you live etc influenced how and what you know?

Which words do you use in your language to express knowledge and knowing?

What does it even mean to know?

How might we possibly begin to define what "knowledge" actually is?

How has your culture, upbringing, gender, point of time in which you live etc influenced how and what you know?

Which words do you use in your language to express knowledge and knowing?

What does it even mean to know?

How might we possibly begin to define what "knowledge" actually is?

|

|

Unit plan: knowledge and a mini mock court trial (also published on My IB)

This unit plan offers a set of three lessons, introducing what it means to know through the means of hands-on mini mock court trial. After the role play activity, students will explore how their role in the trial relates to the different cognitive challenges we experience as knowers. The activity is also used as a stepping stone to introduce Plato's cave allegory. This unit includes a detailed unit plan, video resources, google slides and student handouts.

Unit plan:

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

| tokknow_unit_lesson_plan__1_.pdf | |

| File Size: | 368 kb |

| File Type: | |

Presentations and additional resources per lesson.

|

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

|

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

|

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

| ||||||||||||||||||

| tokknow_lesson1_trial_cards.docx | |

| File Size: | 42 kb |

| File Type: | docx |

| tokknow_unit_lesson_plan.docx | |

| File Size: | 196 kb |

| File Type: | docx |

| tokknow_unit_lesson_plan.pdf | |

| File Size: | 368 kb |

| File Type: | |

|

|

What is Knowledge?

Learning activity: on a large sheet of paper, brainstorm all concepts that come to mind when you hear the word "knowledge". Then, try to use some of these concepts to come up with your own definition of knowledge. You can do this activity as a group, or individually.

It is tempting to grab a dictionary and use the first convenient definition of knowledge. However, in TOK we will not do that. Let's try to think about the idea of knowledge first. If you struggle to define knowledge, do not worry. It is a concept great thinkers have discussed for thousands of years. You don't necessarily need to understand philosophical interpretations of what knowledge is to be successful at TOK. However, it is worth having an exploratory look at these interpretations in order to further nuance our understanding of the concept of knowledge throughout the course.

Traditionally, knowledge has often been defined as justified true belief. This definition is worth unpacking, because of the emphasis it places on belief. The discussion of the role of "belief" in our understanding knowledge has stirred debates amongst some great thinkers. This discussion is particularly relevant now that AI ventures into new territories. Intelligent machines seem to create new knowledge and are now able to learn, without ever being able to genuinely believe in the knowledge they embody. This is interesting stuff for TOK discussions. In TOK, you should avoid using the definition of knowledge as "justified true belief" as a catch-all concept without considering further explanations or implications. However, unpacking the elements of the definition can lead to some interesting explorations. We could wonder, for example, what constitutes a good justification in terms of knowledge, how important belief is when we claim to know something, and how we might define "true" when we discuss the relationship between knowledge and truth.

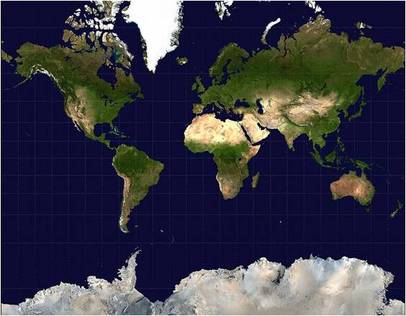

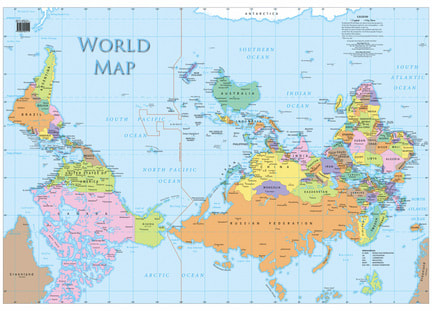

The definition of knowledge as justified true belief may be difficult to grasp. In addition, some aspects of this definition are debatable. This is why the IBO has introduced another "definition." We can also try to understand the concept of knowledge through a metaphor. The TOK guide (both 2015 and 2022 specification) suggests that you could consider the metaphor of "knowledge as a map". This metaphor may not be a perfect "definition" of knowledge, but it can help you understand what knowledge is about. The map metaphor is a little less abstract, perhaps, than the definition of "justified true belief," and in this sense you may "get it" better. "A map is a representation, or picture, of the world. It is necessarily simplified—indeed its power derives from this fact. Items not relevant to the particular purpose of the map are omitted. For example, one would not expect to see every tree and bush faithfully represented on a street map designed to aid navigation around a city—just the basic street plan will do. A city street map, however, is quite a different thing to a building plan of a house or the picture of a continent in an atlas. So knowledge intended to explain one aspect of the world, say, its physical nature, might look really quite different to knowledge that is designed to explain, for example, the way human beings interact." (p.16, TOK Guide, First Assessment 2015). "A metaphor such as this can support rich discussions about knowledge and accuracy, about how knowledge grows and changes, and about the difference between producing and using knowledge. It can also prompt interesting wider reflections on the cultural assumptions behind our understanding of what maps are or should be, or the way that the cartographer’s perspective is reflected in a map. Maps and knowledge are produced by, and in turn produce, a particular perspective." (TOK guide, First assessment 2022).

These old maps represent that sometimes (knowledge) maps are incorrect or incomplete. Sometimes maps have to be re-written and some old representations might get discarded. The same happens with knowledge and how we map what "is out there".

|

|

By now you may have a better understanding of what the concept of "knowledge" means in theory. However, that does not imply that the concept of knowledge is straightforward in practice. On a daily basis, we are continually confronted with what appears to be "knowledge", but how do we know whether those claims about knowledge are well founded? On what basis should we accept or reject something as knowledge? How do we know if something is true? Can we ever truly know what is really out there? These questions are very difficult to answer and it can be frustrating to feel a lack of certainty in our quest for truth. It may be tempting to give up on our quest for truth, because our search seems arguably futile. After all, we are limited by our human frame and human intelligence (or not, when we look at AI and technology?). In addition, history shows us that knowledge changes over time. Can we know anything with certainty given that knowledge seems provisional?

Because of the apparent lack of certainty in our search for knowledge (and truth), some people resort to the position of radical doubt (Lagemaat, 2011). If we doubt everything and everyone, should we even bother getting closer to the truth? This is a difficult position to live with. Others, however, feel that we can come up with valid justifications of knowledge claims and that our continual search for knowledge is invaluable. Indeed, if we think about the progress we have made in the last 500 years, it is clear that we have acquired a lot of knowledge. The road to progress may not always be straight, yet on the whole, we now have a much better understanding of, for example, the natural world, human behaviour and mathematics.

Although we have made massive progress in the production of knowledge. knowledge can be provisional. What is accepted as knowledge today, may be discarded tomorrow. You can easily find examples of knowledge claims of the past that are not accepted anymore. This is true in many areas: some religions have disappeared completely, the geocentric model is obsolete, what is considered "art" has been reviewed repeatedly with changing cultural movements. When you think about this, you may wonder what this changeable nature of knowledge implies for our search for knowledge. You may also wonder whether the search for knowledge is less provisional or dependent upon the beliefs of groups and/or individuals in some areas of knowledge? If so, does this mean that the knowledge they produce is more 'valuable' or "of a better quality"?

Because of the apparent lack of certainty in our search for knowledge (and truth), some people resort to the position of radical doubt (Lagemaat, 2011). If we doubt everything and everyone, should we even bother getting closer to the truth? This is a difficult position to live with. Others, however, feel that we can come up with valid justifications of knowledge claims and that our continual search for knowledge is invaluable. Indeed, if we think about the progress we have made in the last 500 years, it is clear that we have acquired a lot of knowledge. The road to progress may not always be straight, yet on the whole, we now have a much better understanding of, for example, the natural world, human behaviour and mathematics.

Although we have made massive progress in the production of knowledge. knowledge can be provisional. What is accepted as knowledge today, may be discarded tomorrow. You can easily find examples of knowledge claims of the past that are not accepted anymore. This is true in many areas: some religions have disappeared completely, the geocentric model is obsolete, what is considered "art" has been reviewed repeatedly with changing cultural movements. When you think about this, you may wonder what this changeable nature of knowledge implies for our search for knowledge. You may also wonder whether the search for knowledge is less provisional or dependent upon the beliefs of groups and/or individuals in some areas of knowledge? If so, does this mean that the knowledge they produce is more 'valuable' or "of a better quality"?

Reflection: do you think we can measure the quality of an area of knowledge by "how stable" its proposed knowledge is?

|

|

In search for "The truth"

Keep the company of those who seek the truth, and run away from those who have found it.

Vaclav Havel

If you would be a real seeker after truth, it is necessary that at least once in your life you doubt, as far as possible, all things. |

All truth passes through three stages. First, it is ridiculed. Second, it is violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as being self-evident. |

Truth, like gold, is to be obtained not by its growth, but by washing away from it all that is not gold. |

When we question what knowledge is, we will undoubtedly stumble upon the question 'What is truth?' Even though there may not be a satisfying catch-all answer, different theories attempt to offer a response. The coherence theory, correspondence theory and pragmatism each offer some attractive suggestions, but none of them seem entirely satisfying. It is, indeed, very difficult to define what "truth" is. According to the coherence theory of truth, something is true when it fits within our world view, previous knowledge or sentences surrounding the statement. In a court case, for example, we can say that someone is (beyond reasonable doubt) guilty if this statement fits with all the evidence and everything else we know about the situation. This theory of truth is good in the sense that it is not limiting itself to knowledge that can be found in the natural world. However, it is possible to have a statement that seems coherent but is false (just as the person we found to be guilty may be innocent). The correspondence theory of truth states that something is true if the statement corresponds with the natural world and accurately describes the natural world. In this sense, we can say that "the grass is green" is true if there is indeed grass in the world, when the grass is also green and when we have used the sentence structure correctly to describe the state of the grass. The correspondence theory of truth is not very useful to assess the truth value about things that cannot be found in the natural world. However, the kind of thinking represented by the correspondence theory has been pivotal in driving important movements for knowledge such as the scientific revolution. The pragmatic theory of truth claims that something is true when it is useful. The strength of this theory is that it offers an alternative to the (rather limited) correspondence theory and (sometimes inaccurate) coherence theory. There are cases (such as is the case in ethical, legal and political discourse), when the utility of a theory is very important to assess the truth value of statements and cases that cannot be assessed through the correspondence and coherence theory. Nevertheless, it is obvious that mere utility is not always enough to assess the truth value of a statement. When Trump claims that he is "a very stable genius"", this statement may well be useful for himself (and maybe his supporters), but this does not make it true. Even though we should steer away from overly relativistic interpretations of knowledge and truth, Václav Havel's words contain a lot of wisdom: "Keep the company of those who seek the truth, and run away from those who have found it." As Raphael's painting 'School of Athens' demonstrates, the search for what is true has kept thinkers occupied for millennia. We do not expect you to offer "the answer" as to what constitutes "the truth". However, it is important to show an awareness of the complexity of the notion as well as the context (eg area of knowledge) in which you would use it.

Coherence theory of truth |

Correspondence theory of truth |

The Pragmatic theory of truth |

| truth_in_a_post-truth_world.pptx | |

| File Size: | 3923 kb |

| File Type: | pptx |

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

Shadows, reality and truth. |

Reflection: What resources do I have as a knower to help me navigate the world?

Plato used an allegory (story with hidden meaning, based on a comparison) to explain how what we perceive and know as human beings are mere "shadows" of what is really out there. He talked about a story of prisoners chained to a cave, who could only see shadows of what happened in the real world. These shadows were reflected on the walls of the cave. To the prisoners, the shadows were the only reality they knew. They thought the shadows were the real world. When one prisoner escaped and saw the real world, he wanted to tell the other prisoners about his experience. But they did not believe him. The world's shadows is all they knew... and all they wanted to know. The film "The Matrix" also plays with this idea to some extent. In the Matrix, the world we experience is not quite the world as it is. Our reality is, in this sense, some kind of illusion. What kind of things do you think we cannot know, simply because we are human? If you could get the chance to take a pill that showed you the real, bare truth, would you take it? Or do you prefer to (comfortably) stay in our human world of shadows? How do you experience such shadows in your daily life?

|

|

|

|

|

Perspectives and communities of knowers.

Maps and Perspectives

What shapes my perspective?

|

|

|

Activity: draw a map of the world, as accurately as possible.

Which areas did you draw well? Which ones did you struggle with? Why? What type of projection did you use? Why?

Which areas did you draw well? Which ones did you struggle with? Why? What type of projection did you use? Why?

Understanding perspectives is one of the key concepts in Theory of Knowledge. You may well (literally and symbolically) see your world in line with the map below left. You should ask yourself why this is the case. Personally, I was brought up with a Eurocentric world view and despite the generally excellent efforts of my history teachers, the single story I learned at school largely ignored Islamic, Chinese or Native American civilisations. I was left with the idea that my unmapped historical territories would somehow be less important to history as a whole. Nevertheless, the repeated shifts in cognitive paradigms throughout history illustrate that for each interpretation of the world, there may exist another, equally valid world view. In addition to understanding and appreciating different perspectives, students are encouraged to become more sensitive to the theories of knowledge of others in TOK classes. All too often we think in binary oppositions. We oppose West to East, man to woman, reason to emotion, 'developed' to 'primitive'. Whilst doing so, we attach value judgements to each element in the opposite binary pairs; and we usually value our side of the coin that bit more than the other side. We also exclude whatever is in the middle of the continuum and consequently simplify our interpretation of the world, or even "reality". French feminist Cixous claims that this binary thinking finds its origins in patriarchal society. Whatever the cause may be of such thought, it is important to remain open-minded and to steer clear of false dilemmas, which are all too often implicitly embedded in cognitive paradigms of knowledge communities.

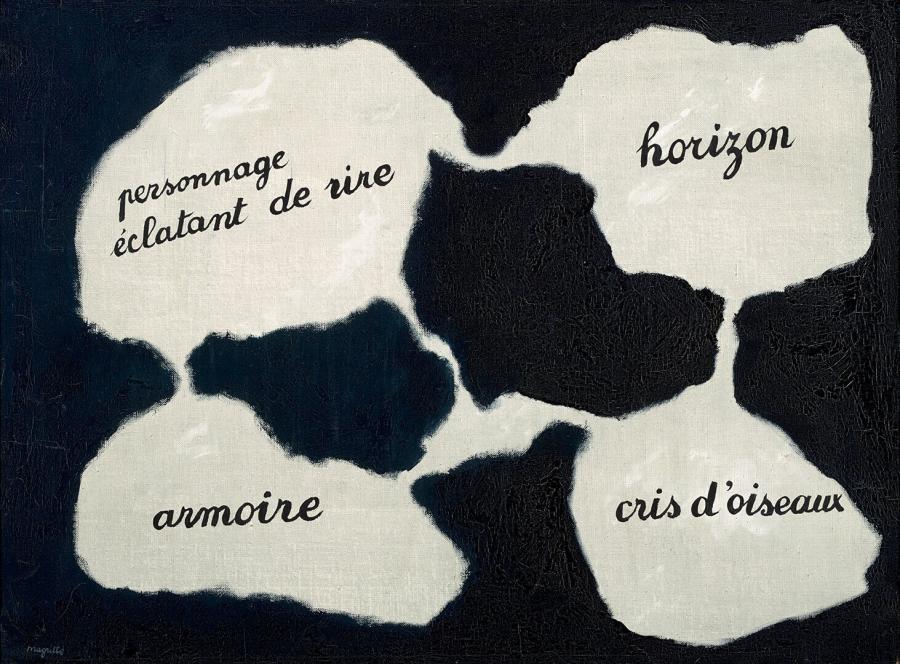

Painter Magritte makes us question through his art how we tend to forget the differences between representation and reality. We can use language and symbols to 'map' reality. Within our language we use words as 'signifiers' to denote something else ('the signified'). But all too often we blend the signifier with the signified. According to Charles Sanders Peirce, we end up thinking through these signs. Just like we end up thinking through maps. And we forget what is really out there. Baudrillard takes this notion even further with his conception of 'the hyperreal'.

Maps (in the broad sense of the word) can be useful as conceptual and practical tools. However, in TOK you are invited to explore to what extent accuracy has given way to simplification through 'maps' in the broad sense of the word. A heightened awareness of the limitations as well as the strengths of the representational capacities of maps is useful in your analysis of the "knowledge as a map" metaphor.

Painter Magritte makes us question through his art how we tend to forget the differences between representation and reality. We can use language and symbols to 'map' reality. Within our language we use words as 'signifiers' to denote something else ('the signified'). But all too often we blend the signifier with the signified. According to Charles Sanders Peirce, we end up thinking through these signs. Just like we end up thinking through maps. And we forget what is really out there. Baudrillard takes this notion even further with his conception of 'the hyperreal'.

Maps (in the broad sense of the word) can be useful as conceptual and practical tools. However, in TOK you are invited to explore to what extent accuracy has given way to simplification through 'maps' in the broad sense of the word. A heightened awareness of the limitations as well as the strengths of the representational capacities of maps is useful in your analysis of the "knowledge as a map" metaphor.

Reflection: how do we use language to "map" the world?

Are there expressions you use in your language that cannot be translated in another language?'

Which new word or expression could you invent to express an idea or "map something"?

Are there expressions you use in your language that cannot be translated in another language?'

Which new word or expression could you invent to express an idea or "map something"?

|

|

Knowers and communities of knowers.

How am I influenced by the different communities of knowers I belong to?

As individuals we know things "independently", but we also get involved with the knowledge around us. Although some knowledge is really our own, "personal knowledge", we should not forget that we belong to one or more communities of knowers. We belong to groups of people who speak the same language, for example. We also belong to groups with shared cultural values. We may even belong to a religious community. As IBDP students, you may have developed a particular academic interest which you will pursue in the future. At some point, you might even belong to a group of experts in this field. All this influences how you make sense of the world and how you navigate the world around you. Your background, your membership to these communities of knowers and simply the place and time in history in which you were born, will shape your values and perspectives.

Within these communities of knowers, knowledge can be created, reviewed, examined and spread. Understanding the importance of communities of knowers and the position of knowers within these communities will help you get an insight into how knowledge evolves. Knowledge that was previously accepted by a large group of people, can sometimes turn out to be wrong. There are circumstances in which we should, but others in which we shouldn't, trust expert opinion. Individual knowers can make significant contributions to knowledge production, but eventually new knowledge should arguably be accepted by a (small) community of knowers of some kind.

Within TOK you will explore how we know as an individual and as a member of a group. It is important to become aware that what you accept as knowledge as an individual member of a group may be heavily dependent upon group membership as such. Speakers of the same language, students of the same 'schools of thought', or members of the same cultural group will often accept similar knowledge claims. Yet, as mentioned before, knowledge is not stable. What we consider to be knowledge within our community today may be discarded tomorrow, and there are many geo-cultural variations in what counts as knowledge today.

Sometimes, we can establish knowledge on our own. We can construct personal knowledge through personal experiences. We can also 'personalise' second hand knowledge by evaluating and assessing what is presented to us as knowledge. It is essential to critically engage with knowledge that has been passed on to you. Authority worship and group think can be dangerous, as the documentary "Five Steps to Tyranny" highlights.

Philosophers and thinkers have created many 'theories of knowledge'. While it is impossible to give you a definite answer to what constitutes true knowledge or even truth, it is worth exploring several perspectives. The BBC A History of Ideas site is a good starting point for further research in this area. The dynamic relationship between knowers and the community they belong to, as well as the dialogue between different perspectives, is often at the heart of the creation of new knowledge; the revision (and hopefully improvement) of our "knowledge maps".

Within these communities of knowers, knowledge can be created, reviewed, examined and spread. Understanding the importance of communities of knowers and the position of knowers within these communities will help you get an insight into how knowledge evolves. Knowledge that was previously accepted by a large group of people, can sometimes turn out to be wrong. There are circumstances in which we should, but others in which we shouldn't, trust expert opinion. Individual knowers can make significant contributions to knowledge production, but eventually new knowledge should arguably be accepted by a (small) community of knowers of some kind.

Within TOK you will explore how we know as an individual and as a member of a group. It is important to become aware that what you accept as knowledge as an individual member of a group may be heavily dependent upon group membership as such. Speakers of the same language, students of the same 'schools of thought', or members of the same cultural group will often accept similar knowledge claims. Yet, as mentioned before, knowledge is not stable. What we consider to be knowledge within our community today may be discarded tomorrow, and there are many geo-cultural variations in what counts as knowledge today.

Sometimes, we can establish knowledge on our own. We can construct personal knowledge through personal experiences. We can also 'personalise' second hand knowledge by evaluating and assessing what is presented to us as knowledge. It is essential to critically engage with knowledge that has been passed on to you. Authority worship and group think can be dangerous, as the documentary "Five Steps to Tyranny" highlights.

Philosophers and thinkers have created many 'theories of knowledge'. While it is impossible to give you a definite answer to what constitutes true knowledge or even truth, it is worth exploring several perspectives. The BBC A History of Ideas site is a good starting point for further research in this area. The dynamic relationship between knowers and the community they belong to, as well as the dialogue between different perspectives, is often at the heart of the creation of new knowledge; the revision (and hopefully improvement) of our "knowledge maps".

This documentary illustrates the dangers associated with group think, which can occur when we only accept the knowledge from our immediate community (and those in charge of it).

|

|

Lecture by philosopher Julian Baggini, who wrote "How the World Thinks". (superb TOK material and recommended further reading).

|

|

So what should we believe?

The Believing Brain

Why we sometimes feel compelled to believe strange things.

The TED talks below by Shermer are very popular in TOK classes. They discuss how and why people sometimes feel compelled to believe strange things. The examples given by Shermer to illustrate human gullibility are certainly entertaining. According to Shermer, we are pattern seeking animals. To guarantee our survival, we have been looking for patterns for centuries (better to be safe than sorry). Shermer argues that we still feel compelled to see patterns, whether they exist or not and he illustrates this in "The pattern behind self-deception". In terms of knowledge production, we should arguably find a good balance between too little and too much imagination. If we have too much imagination, we can find patterns where there aren't any, and this is not very useful. However, without imagination, we miss patterns that exist and we may hamper the production of knowledge.

Recommended further reading: The believing brain (Shermer 2011) and Why people believe strange things.

TOP TIP FOR TED TALKS:If your find it difficult to follow the arguments (especially if English is not your first language), you can always check out the transcripts on the TED websites themselves. If you want to quote a TED talk, click here to find out how.

Recommended further reading: The believing brain (Shermer 2011) and Why people believe strange things.

TOP TIP FOR TED TALKS:If your find it difficult to follow the arguments (especially if English is not your first language), you can always check out the transcripts on the TED websites themselves. If you want to quote a TED talk, click here to find out how.

|

|

|

Reflection: have you ever looked for (or claimed to "discover") patterns when there weren't any?

Lesson idea: "Youtubers and influencers"

On knowledge, belief and opinion.

- Students create a belief continuum ranging from "strongly disbelieve", "disbelieve", over "not sure", and "believe", to "strongly believe"

- The teacher reads out a range of short statements which students place on their personal belief continuum. (Possible Examples of statements: "The earth is round", "there is life after death", "God exists", "Aliens have visited earth at some point in the past", "The theory of evolution", "the size of your skull is an indicator of intelligence", "meditation can cure cancer", "intermittent fasting will make me lose weight"...)

- Discuss why your belief continuum may be different from someone else's (in the classroom, or elsewhere in the world.) Related knowledge questions to drive the discussion:

-Do all claims require evidential support?

- Students select a claim/statement they strongly disbelieve (from the continuum).

- MAIN ACTIVITY: Students create a video in the style of a (famous) Youtuber or influencer to convince the audience of that same claim.

- Discussion:

-What criteria can we use to distinguish between knowledge, belief and opinion?

-How do we distinguish claims that are contestable from claims that are not?

Knowledge in a post-truth age

How do I distinguish between claims that are contestable and claims that are not?

The concept of knowledge is a rather problematic one. We are continually confronted with knowledge claims in our daily lives, but how do we know whether these claims are well founded? From wrinkle creams, to online scams and misguided reports of our colonial history, our lives are filled with all sorts of claims that pretend to be knowledge or fact. But, on what basis should we accept or reject something as knowledge? How do we know if something is true?

|

|

|

|

Some people or entities (such as companies) can be very good at misguiding us. Politicians, for example, can use a particular type of language to manipulate our thoughts. They can pretend to care for the preservation of knowledge, when in fact, they are deliberately trying to do the opposite. This can happen in two ways. They can claim things are not true, when they are. Conversely, they can also convincingly claim something is true, when this is clearly not the case. Trump, for example, has illustrated that it is way too easy to brush "inconvenient truths" off as "fake news". It can be dangerous to disregard facts.

However, this does not mean that we should accept every bit of information that comes our way as genuine knowledge. It is up to us to make good judgement and to critically evaluate the knowledge we encounter. Sometimes this is difficult to judge. Explanations that seem acceptable to us, may not seem acceptable to members of other communities of knowers. It can be frustrating that we cannot know everything. We are human, and we are limited to our human body and mind. There are things "out there" that we cannot (yet) perceive or understand. We could indeed claim that we can never truly know what is really "out there".

However, this does not mean that we should accept every bit of information that comes our way as genuine knowledge. It is up to us to make good judgement and to critically evaluate the knowledge we encounter. Sometimes this is difficult to judge. Explanations that seem acceptable to us, may not seem acceptable to members of other communities of knowers. It can be frustrating that we cannot know everything. We are human, and we are limited to our human body and mind. There are things "out there" that we cannot (yet) perceive or understand. We could indeed claim that we can never truly know what is really "out there".

"The truth" is indeed a very tricky concept that is very difficult to define. And yet, we have gathered and produced an incredible amount of knowledge throughout history. Human beings are also ingenious when it comes to devising methods that can overcome our human limitations. Arguably, it is sometimes difficult to know something with certainty. Indeed, the historical development of disciplines (or areas of knowledge) demonstrates the provisional nature of knowledge. Yet, that does not mean we should abandon our quest for knowledge. Long gone are the days that we should fear the punishment of the Gods for getting closer to the truth (see illustrations below).

Are you brave enough to pursue knowledge?

The stories of the Tower of Babel (left), Prometheus (middle) and Adam and Eve eating fruit from the tree of knowledge (right) all served as warning signs to humans, who were discouraged from expanding their knowledge and skills beyond the "intended human scope". In the story of Babel (left), God punished humans for trying to reach heaven. He did this by creating different languages. Prometheus (middle) was punished cruelly for trying to steal fire from the Gods. Adam and Eve's consumption of the fruit from the tree of knowledge (right), led to "the fall of mankind". Luckily, in most countries in the contemporary world, we should not be afraid to expand our knowledge and question what we know.

Possible Knowledge Questions on the Core Theme

Acknowledgement: these knowledge questions are taken from the official IBO TOK Guide (2022 specification)

|

Scope

Methods and tools

|

Perspectives

Ethics

|