|

|

Scope, methodology and purpose: introduction

The human sciences aim to describe and explain human behaviour of individuals or members of a group. Although the human sciences comprise a wide range of disciplines such as psychology, social and cultural anthropology, economics, political science and geography, they all have common features such as a shared methodology and the overall object of study: human existence and behaviour. Within TOK, history is not included amongst the human sciences. The object of study of history is quite unique because the past is, well... in the past. Consequently, history uses its own methods to gain knowledge about the (recorded) past.

It is quite fascinating how such a wide range of different disciplines within the human sciences aim to acquire knowledge about human behaviour. What psychology aims to explain is very different from, let's say, economics. This will affect the nuances of the methods, concepts and approaches used by each discipline. Nevertheless, the overarching focus of human sciences lies with knowledge about human existence and behaviour.

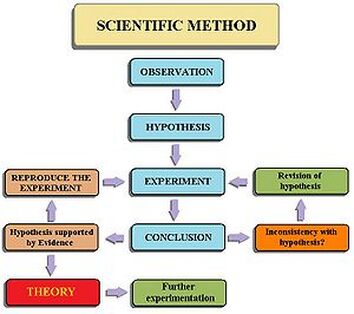

The study of human behaviour is complex in nature and it can be approached through different perspectives. Other areas of knowledge, such as the arts, can also offer insights into human behaviour. A novel like 1984 can, for example, give (imaginary) insights into how people behave in (totalitarian) societies. This novel also offers some powerful reflections on the connection between power, language and politics. Performance artists like Abramovic can show how an audience interacts with their art and this might tell us something more about human behaviour. Human scientists, however, aim to acquire this knowledge through a scientific approach. In this sense, there are obvious overlaps with the natural sciences, where we also use the scientific method. Human scientists use observation, collect data, form hypotheses, aim to test the validity of these hypotheses and possibly falsify them. Theories are accepted if they stand the test of time, and rejected if proven wrong. Human scientists may even uncover laws, such as the law of supply and demand in economics. However, a law in the human sciences does not mean entirely the same thing as a law from the natural sciences. In fact, human scientists face some specific challenges when they apply the scientific method. Firstly, collecting data (through observation) is not that straightforward. Secondly, it is not always easy to falsify and test hypotheses. Finally, bias or hasty generalisations may lead to incorrect knowledge. These problems are not solely confined to the human sciences, but some of them are magnified when we study human behaviour. It would, nevertheless, be foolish to dismiss all knowledge produced by human scientists as "unscientific" or of a lesser quality in se. Good human scientists are aware of these possible pitfalls; they show a critical awareness of the methodology they employ and they use concepts such as "causation" and "certainty" with caution.

It is quite fascinating how such a wide range of different disciplines within the human sciences aim to acquire knowledge about human behaviour. What psychology aims to explain is very different from, let's say, economics. This will affect the nuances of the methods, concepts and approaches used by each discipline. Nevertheless, the overarching focus of human sciences lies with knowledge about human existence and behaviour.

The study of human behaviour is complex in nature and it can be approached through different perspectives. Other areas of knowledge, such as the arts, can also offer insights into human behaviour. A novel like 1984 can, for example, give (imaginary) insights into how people behave in (totalitarian) societies. This novel also offers some powerful reflections on the connection between power, language and politics. Performance artists like Abramovic can show how an audience interacts with their art and this might tell us something more about human behaviour. Human scientists, however, aim to acquire this knowledge through a scientific approach. In this sense, there are obvious overlaps with the natural sciences, where we also use the scientific method. Human scientists use observation, collect data, form hypotheses, aim to test the validity of these hypotheses and possibly falsify them. Theories are accepted if they stand the test of time, and rejected if proven wrong. Human scientists may even uncover laws, such as the law of supply and demand in economics. However, a law in the human sciences does not mean entirely the same thing as a law from the natural sciences. In fact, human scientists face some specific challenges when they apply the scientific method. Firstly, collecting data (through observation) is not that straightforward. Secondly, it is not always easy to falsify and test hypotheses. Finally, bias or hasty generalisations may lead to incorrect knowledge. These problems are not solely confined to the human sciences, but some of them are magnified when we study human behaviour. It would, nevertheless, be foolish to dismiss all knowledge produced by human scientists as "unscientific" or of a lesser quality in se. Good human scientists are aware of these possible pitfalls; they show a critical awareness of the methodology they employ and they use concepts such as "causation" and "certainty" with caution.

|

|

How do we use knowledge acquired by the human sciences?

Human behaviour is fascinating. Knowledge regarding this behaviour is interesting on its own, but it can also be very "useful". Knowledge about the principle of "supply and demand" helps us understand how and why transactions on markets take place and how prices are determined. By analysing patterns and studying things such as debt and money supply, economists can (sometimes) predict economic crises. Insights into psychology can help us deal with emotional difficulties such as depression. Sociological research about gender and status can serve to create more egalitarian societies. All this can ultimately lead to a better, more empathetic world. However, knowledge about human behaviour is not always used for this purpose. It can also be used for selfish motives, to steer and even manipulate people's actions. Companies can use knowledge gathered through market research to influence consumer behaviour, for example. When research into human behaviour is funded by entities that will profit from its findings, the outcome of this research will more than likely be reductionist (the profit aspect) and the methods or purpose may not always be morally sound. We sometimes forget that companies zealously (and rather sneakily) gather information and data regarding our online behaviour. Access to this data is used to form knowledge about our (online) behaviour. Powerful entities, such as states and advertising companies, may benefit from access to this knowledge. Intelligent machines are incredibly efficient at spotting patterns, from which generalisations regarding human behaviour are created. We increasingly come across claims that face recognition technology and AI can identify and even predict human behaviour. This knowledge can be used to create amazing tools such as a machine that can help predict (and hopefully prevent) suicide. However, knowledge gathered through and created by AI can be used for discriminatory purposes. If face recognition promises to spot a potential criminal by analysing the features of your face, a potential employer could use such "calculations" against you. In addition to the obvious ethical considerations, we should not forget that the "discovery" of these patterns may not be as neutral, accurate or free from bias as we might think. For example, in 2017 a paper was published about a new algorithm that can allegedly guess with remarkable (better than human) accuracy whether you are gay or straight by analysing your facial features. It seems tempting to think that the findings are neutral because the algorithm as such is not human. However, human researchers were at the basis of the development of this technology. By leaving out people of colour and making no allowances for transgender and bisexual people, the accuracy of this particular piece of research can be disputed. We can also question how useful or even ethical is it to describe human behaviour through mathematical language. Does apparent "accuracy" come at the price of reductionism? Cases such as the one mentioned above, also re-open the age-old nature versus nurture debate. If we accept that the shape of our face (partly) determines our sexual orientation or disposition towards violent behaviour how much free will do we have? Attempts to reduce human behaviour to a "numbers only game", or a "purely biological" matter, have often gone wrong. In short, knowledge about human behaviour can be used for different purposes. When we assess the quality of knowledge in this area, it is important to evaluate who or what was at the source of the knowledge produced and why the knowledge was produced to begin with.

|

|

Methodology: How do human scientists aim to acquire knowledge?

What is so scientific about the human sciences?

Although there are obvious overlaps between the human and the natural sciences, some special challenges arise in applying the scientific method to the human sciences. The scientific method requires observation, from which we may form a hypothesis. This hypothesis is tested and falsified. The latter often happens through experimentation, although this is not always possible (yet). The observation stage can be quite tricky in the human sciences. Arguably, we can only ever observe the outward manifestations of human behaviour; we have no real objective and direct access to inner thoughts and feelings as such. This makes the situation different from a natural scientist who observes, let's say, the properties of a leaf. MRI's may well give additional information about which parts of the brain react given certain situations or stimuli, but we can never truly get inside a person's mind to figure out what drives his or her behaviour. The very act of observing may also affect the observed. True, this may also be the case in the natural sciences (e.g. the temperature of the thermometer could affect the temperature of an observed liquid), but the effects are sometimes more profound in the human sciences. When people know they are being observed, they may behave differently (think of the behaviour of participants in reality TV shows, for example). Some complex things, such as consciousness or happiness, are also very hard to measure. You may have come across a global happiness index, where countries are ranked according to happiness. But have you ever wondered how we measure happiness? Measuring happiness is very different from how we measure things such as the temperature of a liquid in the natural sciences.

When human scientists have gathered data through observation, they may be able to form a hypothesis, which will then need to be tested. It is not always easy to test the validity of this hypothesis, and both natural as well as human scientists come across obstacles in this area. Nevertheless, assessing the validity of a hypothesis is more difficult within the human sciences. Not all knowledge about human behaviour can be gathered through experimentation within a laboratory style setting (where we can control variables). This is not always desirable nor possible (some behaviours can only be observed in their natural setting). We can never repeat human experiments in exactly the same conditions, if experimentation is at all possible. After all, either the participants will be different, or the same participants will have changed (and have previous knowledge of the experiment). Human scientists may look at the world around them to check if what was predicted by the hypothesis is reflected in reality. However, the very act of predicting (e.g. in economics) may affect the prediction.

In this sense human scientists find it quite difficult to claim with certainty that something is a scientific fact. This is why your psychology teacher may confidently talk about correlation, but less so about causation. Scientific theories (whether natural or human) only survive as long as they stand the test of time. Laws are a little different. In the natural sciences, laws generally speaking do not change over time and they are fairly good at predicting what will happen. Nevertheless, laws in human sciences are not always good at predicting what will happen. In this sense "human sciences usually uncover trends rather than laws" (Lagemaat, 2015).

But does all this mean that knowledge from the human sciences is "of a lesser quality"? Not necessarily. The subject matter of both areas of knowledge is different, so it is not desirable to approach the study of all human behaviour through the exact same methodology as a natural scientist's. Sometimes a natural scientist can offer complementary knowledge that can help explain human behaviour and offer (partial) treatment for things such as depression. However, this may not be possible in other disciplines like economics. The human sciences can explain many things that cannot be explained through other areas of knowledge. In this sense, it would be foolish to reduce the human sciences to only what can be confirmed by the natural sciences merely because we are uncomfortable with the apparent lack of certainty.

When human scientists have gathered data through observation, they may be able to form a hypothesis, which will then need to be tested. It is not always easy to test the validity of this hypothesis, and both natural as well as human scientists come across obstacles in this area. Nevertheless, assessing the validity of a hypothesis is more difficult within the human sciences. Not all knowledge about human behaviour can be gathered through experimentation within a laboratory style setting (where we can control variables). This is not always desirable nor possible (some behaviours can only be observed in their natural setting). We can never repeat human experiments in exactly the same conditions, if experimentation is at all possible. After all, either the participants will be different, or the same participants will have changed (and have previous knowledge of the experiment). Human scientists may look at the world around them to check if what was predicted by the hypothesis is reflected in reality. However, the very act of predicting (e.g. in economics) may affect the prediction.

In this sense human scientists find it quite difficult to claim with certainty that something is a scientific fact. This is why your psychology teacher may confidently talk about correlation, but less so about causation. Scientific theories (whether natural or human) only survive as long as they stand the test of time. Laws are a little different. In the natural sciences, laws generally speaking do not change over time and they are fairly good at predicting what will happen. Nevertheless, laws in human sciences are not always good at predicting what will happen. In this sense "human sciences usually uncover trends rather than laws" (Lagemaat, 2015).

But does all this mean that knowledge from the human sciences is "of a lesser quality"? Not necessarily. The subject matter of both areas of knowledge is different, so it is not desirable to approach the study of all human behaviour through the exact same methodology as a natural scientist's. Sometimes a natural scientist can offer complementary knowledge that can help explain human behaviour and offer (partial) treatment for things such as depression. However, this may not be possible in other disciplines like economics. The human sciences can explain many things that cannot be explained through other areas of knowledge. In this sense, it would be foolish to reduce the human sciences to only what can be confirmed by the natural sciences merely because we are uncomfortable with the apparent lack of certainty.

|

|

How objective can our knowledge about human behaviour be?

How may bias lead to flawed results?

How much evidence is needed before we can make generalisations?

On the whole, scientists aim to be objective because bias can affect the validity of the knowledge they produce. Although it is arguably impossible to be entirely free from bias within the human sciences, it is important to understand where a lack of objectivity may sneak in, and how we can avoid it. A little bit of "personal engagement" can drive the production of knowledge and we sometimes need to use our "self" to interpret the behaviour of others. However, history shows that bias and a lack of awareness of our own perspective can lead to the creation of distorted knowledge.

Human behaviour is difficult to grasp and we may not get to observe this behaviour in its most natural or "neutral" form. The very act of observing may affect what you observe. When cultural anthropologists want to gain knowledge about how communities behave, they may immerse themselves within these communities and "go native". However, their very presence may still affect the way people behave and lead to inaccurate knowledge. In addition, anthropologists may face linguistic difficulties or use their own cultural bias to interpret events, even if this is reduced to a minimum. Something similar happens in psychology. When people actively take part in an experiment, they often behave differently. Clever psychologists and sociologists may devise techniques to disguise the purpose of their experiments. They "trick" participants into thinking they are being tested on something else than what appears to be the case. This may help them come up with more accurate results. An experimental approach to the study of human behaviour can lead to the production of sound and reasonably objective knowledge. This can be illustrated with behavioural economics. Economist Vernon Smith, for example "developed a methodology that allowed researchers to examine the effect of policy changes before they are implemented" (Investopedia.com). There are many aspects of human behaviour, however, that cannot be researched via controlled experiments (where we can control the variables and measure more accurately). These aspects can only be observed in a real-life setting, with less or even no control of variables. There may also be a discrepancy between findings observed in a controlled environment and real life applications. Human behaviour is complex and dependent on numerous factors that may not have been accounted for previously. When we observe human behaviour, we will always observe a small segment of people. From this, we may conclude things about the larger population. Such hasty generalisations may lead to false conclusions. We could conclude things based on a sample section that is really too small, or we may form inaccurate conclusions about other communities based on our own values and behaviours. This is exacerbated by the fact that we cannot always "test" our hypothesis or repeat experiments to falsify previous hypotheses. Bias can also an issue within the natural sciences, but in some cases less so because experimentation may be easier and there is less need to consider things such as values and culture when we produce knowledge in the human sciences.

Human behaviour is difficult to grasp and we may not get to observe this behaviour in its most natural or "neutral" form. The very act of observing may affect what you observe. When cultural anthropologists want to gain knowledge about how communities behave, they may immerse themselves within these communities and "go native". However, their very presence may still affect the way people behave and lead to inaccurate knowledge. In addition, anthropologists may face linguistic difficulties or use their own cultural bias to interpret events, even if this is reduced to a minimum. Something similar happens in psychology. When people actively take part in an experiment, they often behave differently. Clever psychologists and sociologists may devise techniques to disguise the purpose of their experiments. They "trick" participants into thinking they are being tested on something else than what appears to be the case. This may help them come up with more accurate results. An experimental approach to the study of human behaviour can lead to the production of sound and reasonably objective knowledge. This can be illustrated with behavioural economics. Economist Vernon Smith, for example "developed a methodology that allowed researchers to examine the effect of policy changes before they are implemented" (Investopedia.com). There are many aspects of human behaviour, however, that cannot be researched via controlled experiments (where we can control the variables and measure more accurately). These aspects can only be observed in a real-life setting, with less or even no control of variables. There may also be a discrepancy between findings observed in a controlled environment and real life applications. Human behaviour is complex and dependent on numerous factors that may not have been accounted for previously. When we observe human behaviour, we will always observe a small segment of people. From this, we may conclude things about the larger population. Such hasty generalisations may lead to false conclusions. We could conclude things based on a sample section that is really too small, or we may form inaccurate conclusions about other communities based on our own values and behaviours. This is exacerbated by the fact that we cannot always "test" our hypothesis or repeat experiments to falsify previous hypotheses. Bias can also an issue within the natural sciences, but in some cases less so because experimentation may be easier and there is less need to consider things such as values and culture when we produce knowledge in the human sciences.

|

|

Approaches to knowledge about human behaviour

Reflection: In what ways might the beliefs and interests of human scientists influence their conclusions?

Within each discipline, there may be different ways to shed light on human behaviour. For example, within contemporary psychology you can take a psychodynamic, behaviourist or humanist approach. These approaches may co-exist and offer complementary knowledge. In this sense. the inclusion of a range of perspectives may lead to better knowledge. However, sometimes, theories or approaches cannot be reconciled and it appears that previous knowledge (or branches) within a discipline has to be discarded. Phrenology, for example, is no longer considered to give us reliable knowledge within psychology.

|

|

Using MRIs to research the brain in loveWhy do we crave love so much, even to the point that we would die for it? To learn more about our very real, very physical need for romantic love, Helen Fisher and her research team took MRIs of people in love -- and people who had just been dumped. |

PhrenologyDoes the combination of a natural and human scientific approach lead to better knowledge about human behaviour? Phrenology has long been discarded. Do modern MRIs offer a better approach?

|

|

|

The contextual nature of knowledge in the human sciences

Can psychological knowledge be timeless? Does this matter?

How ethical is it for dominant groups to produce knowledge about the behaviour of others?

Should we be able to repeat psychological experiments to claim something with certainty?

How ethical is it for dominant groups to produce knowledge about the behaviour of others?

Should we be able to repeat psychological experiments to claim something with certainty?

Human behaviour is largely context dependent. What drove your great-grandparents to behave a certain way may not affect you. As the world changes, new behaviours will develop. In addition to historical variations, we need to take cultural and geographical variations into account. A theory that explains the behaviour of a Belgian group of teenagers anno 2050, may not at all be useful to explain the behaviour of a group of teens in the Borneo jungle 500 years ago. An IQ test designed for (and by) white males, for example, may not give accurate results elsewhere in the world. We cannot always expect results from human scientific experiments to be replicated in a new situation, because the context will be different. The historical development of psychology as a discipline demonstrates that the methodology of the discipline has changed dramatically over the years. The validity of its methods as well as the actual theories it proposes are continually put to the test. Most people will have heard about Freud, but much of what he 'discovered' has been discarded today, partly because of flawed methodology, partly because some of his findings are simply not relevant in a contemporary context. In this sense, it is difficult to claim that knowledge about human behaviour is timeless and independent of the context in which it was produced.

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

|

|

Ethics and knowledge in human sciences.

To what extent are the methods used in the human sciences limited by the ethical considerations involved in studying human beings?

When we try to get knowledge about human behaviour, we need to keep a couple of ethical considerations in mind. Firstly, the purpose of the knowledge we acquire should be morally justifiable. There are some areas we cannot research for moral reasons. For example, it would arguably be wrong to research the connection between race and certain behaviours such as intelligence and violence because history has shown that (an interest in) such (sometimes erroneous) knowledge has been abused in the past; it can lead to eugenics programmes and even genocides. In addition, we need to ensure that the way in which we gather knowledge is morally justifiable. As always, in TOK we should consider the criteria we might use to decide whether knowledge production is moral or not. Does the outcome of our research ever justify the means? Is it possible to provide a rational basis for ethical decision making when it comes to knowledge production in the human sciences? How might we "define" a morally sound methodology we could use to obtain knowledge about human behaviour?

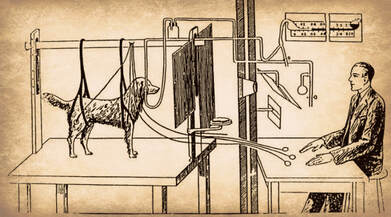

Some of the most interesting psychological experiments conducted in history touch upon dubious ethical grounds. Ivan Pavlov (see Pavlov's dog), for example, used experimental methods to research "conditioning" which many contemporary human scientists now consider unethical. In some cases, we cannot always repeat the experiments due to ethical constraints. One of these examples is arguably the Milgram experiment (see below), in which participants were tested on their willingness to inflict pain on innocent citizens. The results of the Milgram experiment (60's), were ground breaking at the time. Its mind blowing results undoubtedly changed many preconceptions regarding human behaviour. After WWII, it was tempting for the victors to think that things such as the holocaust could only have happened in Germany, that "ordinary" people like yourself would never be able to inflict such cruelties. However, the Milgram experiment shattered this myth. The experiment 'popularised' Arendt's concept of 'the banality of evil' and ordinary citizens became acutely aware of the dangers of authority worship. The knowledge created through this experiment can be used for sound ethical reasons. After all, it makes us more aware of the potential harm we might inflict on others, which could prevent future immoral actions. However, throughout the conduction of the Milgram experiment, participants were not told that they would be tested on their willingness to inflict pain on innocent citizens. Instead, they were told they had to take part in a memory experiment. When the participants found out how willing they had been to inflict pain, some suffered serious emotional distress. We could wonder whether it is justifiable to conduct such experiments for moral reasons. The Stanford Prison experiment by Zimbardo is another example of an experiment which pushed the moral methodological limits. In this experiment, some participants became quite cruel towards their peers, which led to emotional distress.

So what does this imply? Without the ability to repeat an experiment, we may not get enough data to be statistically relevant. Ethical limitations may prevent us from gathering knowledge about human behaviour because we cannot always repeat these experiments. It may also be morally wrong to gather information about human behaviour in some situations. In addition, knowledge about human behaviour can be used for immoral motives. It is not always easy to set the criteria to decide whether knowledge production about human behaviour is moral or not, but it is important to be aware of the possible ethical limitations.

Some of the most interesting psychological experiments conducted in history touch upon dubious ethical grounds. Ivan Pavlov (see Pavlov's dog), for example, used experimental methods to research "conditioning" which many contemporary human scientists now consider unethical. In some cases, we cannot always repeat the experiments due to ethical constraints. One of these examples is arguably the Milgram experiment (see below), in which participants were tested on their willingness to inflict pain on innocent citizens. The results of the Milgram experiment (60's), were ground breaking at the time. Its mind blowing results undoubtedly changed many preconceptions regarding human behaviour. After WWII, it was tempting for the victors to think that things such as the holocaust could only have happened in Germany, that "ordinary" people like yourself would never be able to inflict such cruelties. However, the Milgram experiment shattered this myth. The experiment 'popularised' Arendt's concept of 'the banality of evil' and ordinary citizens became acutely aware of the dangers of authority worship. The knowledge created through this experiment can be used for sound ethical reasons. After all, it makes us more aware of the potential harm we might inflict on others, which could prevent future immoral actions. However, throughout the conduction of the Milgram experiment, participants were not told that they would be tested on their willingness to inflict pain on innocent citizens. Instead, they were told they had to take part in a memory experiment. When the participants found out how willing they had been to inflict pain, some suffered serious emotional distress. We could wonder whether it is justifiable to conduct such experiments for moral reasons. The Stanford Prison experiment by Zimbardo is another example of an experiment which pushed the moral methodological limits. In this experiment, some participants became quite cruel towards their peers, which led to emotional distress.

So what does this imply? Without the ability to repeat an experiment, we may not get enough data to be statistically relevant. Ethical limitations may prevent us from gathering knowledge about human behaviour because we cannot always repeat these experiments. It may also be morally wrong to gather information about human behaviour in some situations. In addition, knowledge about human behaviour can be used for immoral motives. It is not always easy to set the criteria to decide whether knowledge production about human behaviour is moral or not, but it is important to be aware of the possible ethical limitations.

|

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

| ||||||

|

|

The applicability of laws and theories

The curious task of economics is to demonstrate to men how little they really know about what they imagine they can design.

Friedrich August von Hayek

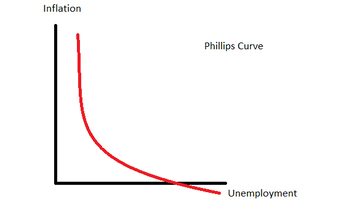

Sometimes human scientists create theories or models that look good on paper, but are not always applicable in practice. For example, economists may gather data and create a model for economic forecasting. However, human behaviour is not always predictable and we sometimes make mistakes with our predictions or how we apply previous knowledge (from models) to new scenarios. For example, some economic crises were not widely predicted. On top of this, we may misinterpret the connection between causation and correlation. It is easy for to fall in the trap of the "post hoc ergo propter hoc" fallacy, whereby we mistake mere correlation with causation. To illustrate this fallacy, let's look at the following example. It is a fact that towns with more churches have more prostitutes. You can come up with all sorts of causal explanations for this phenomenon: maybe there were more prostitutes to begin with, which led to the need for more churches to be built, so the "sinners" could get redemption? Or, maybe there were too many churches to begin with. The strong presence of the church might make men feel repressed, which, combined with less sexual activity due the overly pious wives, would have led to the increased presence of prostitutes? In reality, towns with more churches have more butchers, more schools, and more prostitutes... in short: more of everything. There is no causal relation. There is only a correlation. If we confuse correlation with causation in the human sciences, we get erroneous knowledge. Richard van De Lagemaat (Theory of Knowledge for the IB Diploma, 2015) explains this through the example of the Phillips curve in economics. Economist Phillips suggested in the 1960s that there was a "stable relationship between the rate of inflation and the rate of unemployment." (Lagemaat, 2015). Some governments "concluded from this trend that they could reduce unemployment by allowing inflation to rise" (Lagemaat, 2015). However, this did not work and "many countries ended up with both rising inflation and rising unemployment' (Lagemaat, 2015). Although the Phillips curve showed a correlation between the two aspects, there was not necessarily a relationship of causation.

Theories in the human sciences are often good at explaining things as they happen. We can sometimes test the validity of these theories, either through a controlled environment or in a real world setting. However, such experiments are not foolproof and cannot take all variables into account. These theories do not guarantee that the outcomes will be the same for similar scenarios in the real world. When it comes to laws in the human sciences, we should be particularly careful with the predictive power of these laws. Perhaps it is best to speak of trends rather than laws.

Theories in the human sciences are often good at explaining things as they happen. We can sometimes test the validity of these theories, either through a controlled environment or in a real world setting. However, such experiments are not foolproof and cannot take all variables into account. These theories do not guarantee that the outcomes will be the same for similar scenarios in the real world. When it comes to laws in the human sciences, we should be particularly careful with the predictive power of these laws. Perhaps it is best to speak of trends rather than laws.

|

|

Using polls and questionnaires as a means to get data and information?

As seen previously, it is not always easy to get information about human behaviour through experimentation. This is an issue across the disciplines within the human sciences. Sometimes it is not possible to do experiments, and sometimes the sample we can gather through experimentation is simply too small. One way around this, is the use of questionnaires and polls. This type of data collection allows us to reach a wider audience. But questionnaires are not always reliable for a multitude of reasons. Firstly, the questionnaires still target a fairly small segment of society, i.e. the people who have received your questionnaires and bothered completing them. Teachers who complete a master in education, for example, will often gather data for their research within their own schools, and even within these schools only a certain type of teacher or student will bother completing the questionnaires. In this respect, there may be selection bias. Secondly, people do not always respond to questionnaires truthfully. For example, people often like to boast about and exaggerate the regularity of their sexual performances or minimise bad habits such as alcohol or tobacco use. We are not always honest with ourselves and responses in questionnaires reflect this. Going back to the Milgram experiment, it is doubtful whether participants would have answered "yes" in a poll asking whether they would have delivered electric shocks if learners got the answer of the memory test wrong. We also tend to overestimate our strengths and underestimate our weaknesses. In short, we seem quite good at deluding ourselves. For example, research shows that we generally think that we are better looking than we are (the bad news), but we don't always realise this (the good news, if you can call it that way). On top of all this "delusion and dishonesty'" some people also like to figure out what the purpose of the questionnaire is, and then shape their answers to suit this purpose (even though they might not consciously be aware of this fact). Thirdly, the language in questionnaires may be misleading and questions could be loaded in nature. Good human scientists avoid this, but it can be very difficult to compose both truly neutral and encompassing questions for questionnaires. Multiple choice questionnaires may not include room for your particular answer (that you would like to give), which, again may lead to inaccurate data selection.

Lesson idea: the perfect questionnaire?

On measuring, data collection and sampling in the human sciences.

ACTIVITY: You are a human scientist tasked with gaining knowledge about the behaviour of students and you will be able to use students in your TOK class to conduct your research. Your teacher will choose which aspect of human behaviour you should focus on. This could be related to group behaviours, decision making, market preferences, happiness or well-being (in times of Covid-19), peer pressure, learning habits etc.

- How could you measure the above?

- If you were to compose a questionnaire, what kinds of questions could you ask?

- What kinds of generalisations could you make based on the (small) sample size?

- How might you use statistics to reveal knowledge?

Follow-up discussion:

How might the language used in polls and questionnaires to gather information influence the conclusions that are reached?

How does the use of numbers, statistics, graphs and other quantitative instruments affect the way knowledge in the human sciences is valued?

Are observation and experimentation the only two ways in which human scientists produce knowledge?

How might the language used in polls and questionnaires to gather information influence the conclusions that are reached?

How does the use of numbers, statistics, graphs and other quantitative instruments affect the way knowledge in the human sciences is valued?

Are observation and experimentation the only two ways in which human scientists produce knowledge?

Making connections to the core theme, as suggested by the TOK Guide

- If two competing paradigms give different explanations of a phenomenon, how can we decide which explanation to accept?

- Are we more prone to particular kinds of cognitive biases in particular disciplines/ areas of knowledge compared to others?

Suggested knowledge questions on the Human Sciences

Acknowledgement: The knowledge questions are taken from the TOK Guide, 2022 Specification.

|

Scope

|

Perspectives

|

|

Methods and tools

|

Ethics

|