God is Light, Truth, Life. He is Love. He is the Supreme Good.

Mahatma Gandhi

Discussion based on Gandhi's quote: What is God? What knowledge can religion bring us?

|

|

Introduction

The history of mankind shows that religions have been (and continue to be) important sources of knowledge for a large amount of people. Indeed, many people resort to their religion to make sense of the world. We have previously seen that we can understand the concept of knowledge through the map metaphor. However, if knowledge is a map, what is the territory that religion represents?

Religions offer explanations for the reason for our existence, guidance on how we should live our lives, clarifications on what drives human behaviour, as well as explanations about the natural world. In short, it seems that religions can offer us a huge amount of knowledge. And that exactly, can explain their attraction. The scope of the knowledge they offer seems to be quite encompassing at first sight. Religious knowledge may even offer purpose to our lives. Some people believe that religions can offer answers to almost everything, that religions are the one and only "knowledge map" you should possess. However, the true extent of this scope will depend on your perspective and whether or not you accept the knowledge a religion proposes. In reality, the relationship between believers and the knowledge offered by their religions is complex and incredibly varied. Some people will resort to religions to "merely" fulfil a psychological need, others to offer guidance regarding the bigger questions in life, perhaps in times of helplessness. Some believers may find answers to scientific questions within religions, whereas other people look at religion for definitive moral guidelines through which to live their lives. Within TOK, it is important to analyse and examine how religions can offer us knowledge, as well as the extent to which this might (not) be possible.

Religion is something we are often passionate about. In this respect, it is important to keep our TOK discussions focused on knowledge (and not simply about personal taste or opinion). Arguably, atheists could question to which extent religion can offer genuine true knowledge rather than just belief. Nevertheless, one should understand that throughout time, many peoples and cultures have organised their lives around religion. This is significant. We may find the existence of the multiplicity of religions somewhat puzzling. How can we reconcile such a variety of perspectives and (sometimes absolute) claims? In addition, some religions have disappeared from the earth, whereas over time, others have come into existence. If the very existence of a particular religion is not timeless and constant, how can they claim to possess true and timeless knowledge? Some religions have also evolved over time, with schisms (such as the birth of Protestantism in Christianity) representing new knowledge and interpretation. In this respect, it might be interesting to examine the (possibility of) perspectives within a particular religion. Very often these different "streams" stem from disputes regarding the knowledge these respective religions offer. This is excellent TOK material.

Religions often aim to answer some of the bigger questions in life, such as the reason for our existence, human suffering, and the universe's mysterious ways. Religions can be defined as "systems of faith that are based on the belief in the existence of a particular god or gods, or in the teachings of a spiritual leader" (Oxford Dictionary). However, there exist several fundamentally different views of what this means in practice. Theism claims that the universe is created and ruled by a powerful, omnipotent God. Amongst the major world religions, Judaism, Islam and Christianity are examples of theistic religions. Some religions are monotheistic, and others are polytheistic. Christianity, for example, is monotheistic. However, it also postulates the somewhat complex concept of a "Trinity", including "The Father", "The Son" and "The Holy Spirit". A Pantheistic view of religion, on the other hand, draws on the notion that God is everything and everything is part of God. Taoism could be defined as pantheistic (although in practice, the distinction between polytheitic, monotheistic and pantheistic relgions is less solid and more nuanced).

Agnostic knowers neither accept nor deny the existence of God or a higher reality. They are conscious of their 'ignorance', which is an interesting point of view from a TOK perspective.

Religions often aim to answer some of the bigger questions in life, such as the reason for our existence, human suffering, and the universe's mysterious ways. Religions can be defined as "systems of faith that are based on the belief in the existence of a particular god or gods, or in the teachings of a spiritual leader" (Oxford Dictionary). However, there exist several fundamentally different views of what this means in practice. Theism claims that the universe is created and ruled by a powerful, omnipotent God. Amongst the major world religions, Judaism, Islam and Christianity are examples of theistic religions. Some religions are monotheistic, and others are polytheistic. Christianity, for example, is monotheistic. However, it also postulates the somewhat complex concept of a "Trinity", including "The Father", "The Son" and "The Holy Spirit". A Pantheistic view of religion, on the other hand, draws on the notion that God is everything and everything is part of God. Taoism could be defined as pantheistic (although in practice, the distinction between polytheitic, monotheistic and pantheistic relgions is less solid and more nuanced).

Agnostic knowers neither accept nor deny the existence of God or a higher reality. They are conscious of their 'ignorance', which is an interesting point of view from a TOK perspective.

|

The idiosyncratic nature of proof, validity and rationality in religion, led some people to take an atheist stance. 'An atheist denies the existence of a creator God and believes that the universe is material in nature and has no spiritual dimension.' (Lagemaat, 2011). Whether or not you accept religious knowledge may depend on the community of knowers you belong to, which is in its turn influenced by individual and shared memory, language, and emotion. Your religion could play a role when you make value judgements. For example, we resort to religion to give us moral knowledge, we may rely upon faith rather than reason to make ethical decisions. However, does religion truly provide a way to systematise concepts of right and wrong? |

So how should we understand "proof", "evidence" or "a reasonable explanation" in religion? How do we even begin to prove the existence of God? What constitutes a reasonable explanation for a religious claim? Is it even possible to offer good "evidence" when it comes to religion? Arguably, this is where it gets tricky. However, that does not mean that evidence is totally irrelevant within religion. For example, you might not accept the evidence offered by those who propose religious claims, but these claims are still founded upon idiosyncratic evidence of some sort. When we discuss knowledge and religion, it is important to evaluate how religious knowledge might be obtained and the methodology that underpins this quest; otherwise the analysis risks superficiality. In this sense, it would be better to evaluate TOK concepts such as "proof", "evidence" and "explanations" within the context in which they are applied. For example, you could question what might be understood under "a reasonable explanation" within religion, and then further discuss whether this might differ from other AOKs. You may wonder whether all knowledge claims should be open to rational criticism. In addition, you could question whether the true purpose of religion is to offer explanations that are by and large reserved for other AOKs, such as the natural sciences.

Likewise, we could also wonder to what extent scientific developments have the power to influence thinking about religion. Religion and science often clash because the ways in which they aim to understand the world are arguably intrinsically opposed. This gets to the core of the importance of the 4 elements that intertwine our course: methods & tools, scope, ethics and perspectives. In that respect, we might resort to religion to offer us knowledge about some aspects of reality, whilst employing other AOKs (such as sciences) to explain others. Some scientists, such as Brian Heap, use religion to organise their lives, with a strong moral focus. However, this does not mean that both AOKs are interchangeable. Arguably, using religion to explain scientific facts and vice versa is missing the point of what religion is all about. In that respect, it may come as no surprise that some leading scientists and theologians reject the notion of Intelligent Design whilst calling it “neither sound science nor good theology.” (ISSR). Perhaps the true appeal of religion lies in the fact that it aims to resolve problems that other areas can't resolve. Religions propose knowledge that is quite different in nature and scope. They consider difficult, often existential, questions that may not have a definite answer.

To what extent do scientific developments have the power to influence thinking about religion?

Does religion try to resolve problems that other areas can’t resolve?

| _______religion_gk.pptx | |

| File Size: | 744 kb |

| File Type: | pptx |

| cognition_culture_and_religion_surveying.pdf | |

| File Size: | 350 kb |

| File Type: | |

Religion, language and knowledge.

Much religious knowledge is second-hand knowledge, that has been passed down through the generations. This is often in the written form, although it can also happen orally. Given that many religions are old, it is sometimes difficult to interpret the original meaning of religious texts. Language evolves over time and some languages have even disappeared. On top of that, religions have spread around the globe and with that, we are also faced with the problem of language in translation. Sometimes "corrupted versions" of religious texts have been appropriated and built upon. Attempts to go back to the original source aim to overcome this obstacle to knowledge. Occasionally, we hear about "discoveries" of mistranslations. The interpretation of the true meaning of religious texts, and the knowledge they embody, is much discussed by theologians, historians, linguists and "religious practitioners".

As seen above, to believers, religious evidence can come in the form of language. This is usually in the written form through texts such as the Bible, Torah, Koran etc. One issue with using (inspired) language as proof for the existence of God, is that you may end up with circular reasoning. In this sense, using language as religious evidence or proof may not be successful. However, that does not mean religious language is necessarily meaningless.

Although it is arguable whether we should use religious language as evidence for the existence of God (and value of our religion), we should consider the important role language plays within religion. Language can articulate a religious experience, reveal religious knowledge (through texts), disseminate religious knowledge (spreading the world) and even enforce faith. Language does indeed play a pivotal role in passing on religious knowledge, which is heavily dependent on cultural, historical and geographical factors. Language can also be used to enhance faith, for example through prayers, chanting and song. Interestingly, the very linguistic act of saying "I believe" actually feeds one's belief (e.g. "the Creed).

A recurring debate within religion is how "literal" we should take its claims or explanations. For example, when we read in Genesis how God created the world in 6 days (with the 7th devoted to rest), some believers will use these verses to refute the Theory of Evolution. However, many believers today will resort to analogies or metaphors to reinterpret similar scriptures. In this way, religious knowledge can survive when new scientific knowledge contradicts the literal interpretation of its words. However, the use of analogies or metaphors is not only a matter of re-interpreting previous religious knowledge (or texts). In fact, many religions deliberately make use of analogies and metaphors. Jesus's teachings in The Bible, for example, often come in the form of parables, which were subsequently discussed with his disciples (and later on also in church). In Buddhism, as well, you can see examples of a similar use of metaphor. Religions often have a pedagogical function, and anaologies are very useful in this sense. In TOK, we might explore the role of analogy and metaphor in the acquisition of religious knowledge.

|

|

Religion, proof and knowledge

Reflection: Is certainty any more or less attainable in religion than it is in the arts or human sciences?

It is particularly interesting to discuss the role of evidence and proof within religion, as this is excellent TOK material. When we try to prove knowledge offered by religions through the kinds of evidence we would expect within, let's say, the natural sciences, it often goes wrong. In fact, attempts to use empirical evidence, as well as rationalisations (eg post hoc ergo propter hoc and circular reasoning) are often flawed. We may also see patterns where there are none. For example, Newton, however great his scientific genius, also had a clear esoteric interest. In addition to his interest in alchemy, he looked for "secret patterns and messages" in the bible. These attempts were seriously flawed and did not lead to valid knowledge or insights. Perhaps his attempts to reconcile religious and scientific methodology were at the core of this problem.

Personal, religious experience plays an important role in many religions around the world. The Kogi Shaman (left) interacts with the spirits through altered states of consciousness. In Voodoo religions, "posession" (by loa) is desired. In a ceremony guided by a priest or priestess, this possession is considered a valuable, first-hand spiritual experience and connection with the spirit world. In animism, there is no clear distinction between the spiritual and the physical.

As seen above, some people claim that "language" (eg the scriptures) offers sufficient evidence for religious claims. However, we have also discussed how using "inspired language" as proof can be problematic. Another form of evidence might come in the form of, what is commonly called, "religious experience". This religious experience is a first-hand (often life-changing) experience of God, which, to those how experienced it, constitues evidence for the existence of God. Although this experience will involve an emotive response, a religious experience is not just a "feeling". It is an experience of a religiously significant reality (Stanford). This (often sensory) experience may be very real to those who live it, although the experience may be internal to them. In this sense, there is a strange dynamic between the internal religious experience (of the outside world), that feels verifiable at the same time. Although religious experiences are not just feelings, emotions do play a role in the response to the experience (and the very existence of the experience itself).

So what about empirical verification? This is where it gets a little tricky. For example, logical positivists argue that true knowledge can only be obtained through empirical or logical/linguistic verification. Logical positivists are sceptical of theology, as there is no place for it in their empirical, logical and linguistic theory of knowledge. This sort of thinking permeates much of contemporary discourse. We crave empirical and logical proof, and religions cannot always offer this. When scientific claims based on empirical grounds have challenged religious claims, this has not always been received well, as the Galileo affair demonstrates. One might, however, argue that empirical justifications are irrelevant in the context of metaphysical knowledge claims. Maybe we are missing the point of religion when we seek to emulate and apply methodologies from other areas of knowledge to religion? Perhaps religious knowledge does not require the same kind of proof as we expect from other areas of knowledge. And, if so, what does this imply for the kind of knowledge religions can give us?

Religious proof, validity and justification remain key concepts within many debates around knowledge in religion. We could question whether religion is a matter of imagination in order to fulfill a psychological need, or whether faith requires proof at all. Perhaps faith, intuition, language and emotion lead us to religious knowledge, regardless of what empirical evidence (or reason) seems to show us? Kant opposes a rationalist and empirical understanding of God whilst arguing for a metaphysical and moral approach to religious philosophy. His is often contrasted with Hume in his view of religion and morality. Atheists claim that faith and reason cannot be reconciled and according to Freud, religious faith is an irrational wish fulfilment (Lagemaat, 2011).

Is the role of personal experience different in religion compared to other themes and areas of knowledge?

You will believe this!

Some religious knowledge claims seem rather dogmatic in nature. In some communities, blasphemy and apostasy were (and still are) punished by the death penalty. Are there other areas of knowledge were the refusal to accept their knowledge can be punished by death? Some religions allow for varying interpretations regarding the nuances of texts and their metaphors. But very few religions are open to a genuine debate regarding the very core of the knowledge they represent. The foundations of religious knowledge rarely seem to be revised when new knowledge comes to light. When very strong discussions about the nature of knowledge within a particular religion occur, this generally leads to the creations of new sub-branches within a religion (e.g. the birth of Protestantism) or an altogether new religion (e.g. the birth of Christianity) rather than the rewriting of the original religious knowledge map. The incredible variety of religious beliefs, both currently and historically, may lead some to doubt the absolute nature of religious truth. Religious pluralism explains this diversity as different aspects and 'guises leading to the same truth. Ethically, this position seems acceptable, but it may also lead to some philosophical and theological paradoxes.

|

|

A human basis of religion?

Atheists often point out the problems with anthro-pomorphic interpretations of God, which occur within most (institutionalised) religions. If you believe in God, do you think of God in terms of gender? Ethnicity? Does your God resemble a human being in any way? If so, does your God belong to your 'knowledge community'? Why? It is indeed quite difficult to think of God in terms that are completely unrelated to our physical world. What is the role of anthropomorphic analogies in religion? Is true religion unrelated to our physical experience, given that it deals with metaphysical issues? If so, is there any point in 'believing'? One could argue that we see what we want to see and see what we see from a human perspective. Michael Shermer explores some anthropomorphic interpretations of visual stimuli at TED. Yet, should the problem of anthropomorphism automatically lead to scepticism in the field of religion? Somewhat related to the anthropomorphic interpretations of God is the importance of human experience in the context of religion. Some people go through intense religious experiences at some point in their lives and some have described something similar when going through a 'near-death experience'. Other believers claim to have witnessed miracles. These miracles often influence the faith of other believers and they have been described in religious texts. Hume refutes the notion of miracles and many philosophers have tried to steer away from an all too human interpretation of God.

What difficulties are presented by using human language to discuss religious claims?

|

|

Paradoxes

Is it possible to think about God without resorting to anthropomorphism? 'Some philosophers paint God as an 'omnipotent (all powerful), omniscient (all knowing) and omniamorous (all loving) creator of the universe' (Lagemaat, 2011). Yet, such concepts may lead to religious paradoxes. The paradox of omnipotence is the most widely discussed. But also concepts such as suffering (particularly relevant to Christianity) could seem paradoxical. If Christ died to relieve suffering in the world, why is there so much suffering? If God is omnipotent and does aim to relieve suffering, why is the world as it is? Richard van de Lagemaat also discusses the 'paradox of change' and the 'paradox of free will' in his course companion. The paradoxical nature of religious philosophy certainly provides much food for thought: entire courses at top universities in the world are devoted to its discussion and analysis.

|

|

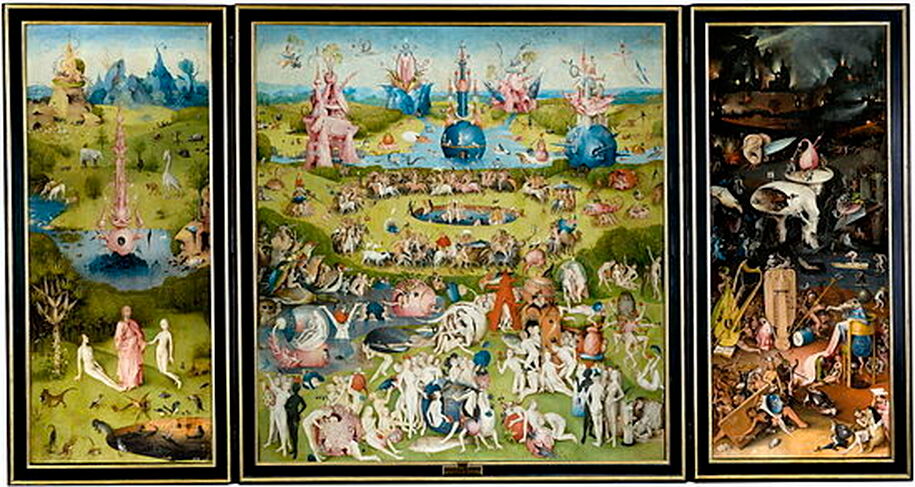

Religion and Ethics

Some people trace their ethical code back to religious books of some kind. The world's religions provide moral inspiration for many people, yet the Greek philosopher Plato was not convinced that we could derive ethics from religion. He felt that our moral values defined whether or not we should accept religion and not the other way around. What do you think? Does your religion define your notion of ethics or do you accept or reject your religion due to your ethical foundations? Morality and ethics have been the subject of philosophical, political and religious discussions for centuries. In addition, ethics provided material for authors and artists. Hieronymus Bosch's painting 'The Garden of Earthly Delights' may be old, but it still appeals to contemporary viewers, not in the least due to the reflections it provokes. Many cultures and religions are obsessed with the idea of purity and excess is often defined as sinful. But why is this the case? Does this idea merely have contextual (historical) foundations (such as the idea of avoiding pork)? We may all have a gut instinct about what's right or wrong, but it may be worth unpicking where this comes from. Is it rooted in our religion, culture or upbringing? Or does it stem from a common compassion and humanity? Why does one find gay marriage completely unacceptable, whereas someone else claims it is a human right? Are we always 'reasonable' or perhaps sometimes too rational when defining what is morally acceptable? Are we guided by the stories our tradition or religion have passed on to us through language? Where do emotions we use to form moral judgements, such as disgust and fear, come from? The community of knowers you belong to strongly influences your sense of morality. Nevertheless, the very existence of the vast range of religions may undermine the absolute claims they often propose. Although the latter does not advocate moral relativism, it should lead us to open up discussions regarding extreme or fundamentalist moral views.

Activity:

According to the standard list, the 7 cardinal sins are pride, greed, wrath, envy, lust, gluttony and sloth.

Now make your own "top 7 of personal sins". Which type of sin do you succumb to most? Which one less so?

Do you agree with the notion that pride would be the most deadly of them all? Why (not)?

According to the standard list, the 7 cardinal sins are pride, greed, wrath, envy, lust, gluttony and sloth.

Now make your own "top 7 of personal sins". Which type of sin do you succumb to most? Which one less so?

Do you agree with the notion that pride would be the most deadly of them all? Why (not)?

|

|

Too much knowledge?

Many religions postulate that human beings should somehow "know their place" and "not know too much". Several religious texts offer a warning to those who try to get too close to the Gods. Hubris was already frowned upon in ancient Greek Mythology, as illustrated by Prometheus' cruel punishment for stealing fire from the Gods. In Christianity, similar quests for knowledge would come under the deadly sin of "pride", which is considered the worst sin of all. And indeed, at the very core of the Bible, the fall of mankind was caused by Adam and Eve eating the forbidden fruit from the tree of knowledge (of good and evil).

Interestingly, such thinking still permeates current debates about the limits of our human quest for knowledge. This is especially the case when it comes to new scientific or technological developments. The development of knowledge in the natural sciences is subject to ethical, but also religious considerations. For example, many people feel trepidation regarding gene editing, stem cell research, or the extension/termination of life. It is interesting to analyse where such feelings come from. Are they based on generalisable ethical principles, or rather rooted in cultural and religious traditions?

Interestingly, such thinking still permeates current debates about the limits of our human quest for knowledge. This is especially the case when it comes to new scientific or technological developments. The development of knowledge in the natural sciences is subject to ethical, but also religious considerations. For example, many people feel trepidation regarding gene editing, stem cell research, or the extension/termination of life. It is interesting to analyse where such feelings come from. Are they based on generalisable ethical principles, or rather rooted in cultural and religious traditions?

|

|

Under what circumstances (not) to accept religious knowledge?

Reflection: To what extent do scientific developments have the power to influence thinking about religion?

Critics of religions often argue that religions do not have sufficient credible evidence to support their claims. Nevertheless, you can argue that this is missing the point of what religion is all about. If we consider knowledge to be a map, you might argue that religion is mapping a very different territory compared with, let's say, the natural sciences. Sometimes it seems that knowledge maps from religions and the natural sciences contradict each other. Evidence from the natural sciences, for example, contradicts the notion of intelligent design. We can try to rationalise these contradictions by playing with the language of religious texts: we can widen the meaning of translated phrases, metaphors and imagery. We can also connect the unconnected to make religious knowledge match with new scientific findings. However, these types of rationalisations are not always convincing. We could, however, argue that there is no need for such (scientific) evidence in religion because the knowledge it tries to map is very different in nature. Maybe the whole point of religions is to look at the world (and beyond) in a different way? Perhaps religion tries to resolve problems that areas can't resolve?

Nevertheless, what should we do when knowledge from religions clearly contradicts knowledge from other areas? Can these contradictory claims and knowledge maps co-exist? Or, does the existence of religious knowledge annihilate scientific knowledge and vice versa? The latter has led to much discussion between scientists, believers, and atheists. This discussion is particularly relevant when it comes to deciding what should be part of the school curriculum. Is it possible to study (and believe/accept) knowledge from religion alongside the natural sciences? How do we approach themes such as, let's say, the theory of evolution alongside intelligent design? Can we truly teach them alongside each other and claim they are equally valuable?

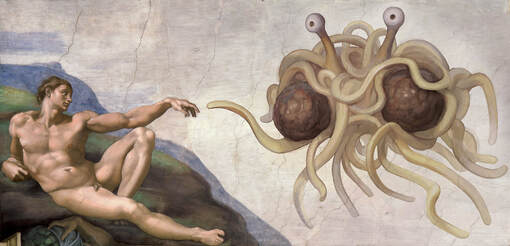

Another important point to consider is that religious knowledge is highly dependent on (dominant) culture. What makes one religion credible and another not? Can there be religious knowledge that is independent of the culture that produces it? Historically, some religions have disappeared and new ones will likely come into existence in the future. On what basis do we decide whether a religion is a genuine religion or merely a cult? What is the difference? How has our understanding and perception of religious knowledge changed over time? The lesson on "Pastafarianism" (see illustration above regarding "The Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster) allows you to explore these ideas further.

| pastafarianism.pptx | |

| File Size: | 2281 kb |

| File Type: | pptx |

Making links to the core theme, as suggested by the TOK Guide

- How does our own theism, atheism or agnosticism impact our perspective?

- Do you agree with Carl Sagan’s claim that “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence”?

- How can our respect for a religion or culture be reconciled with the condemnation of specific practices within that religion or culture?

Knowledge questions on "knowledge and religion"

Acknowledgement: the suggested knowledge questions are taken from the TOK guide, 2022 specification.

|

Ethics

|

Methods and tools

|

|

Perspectives

|

Scope

|