Within this optional theme, you will explore the connection between language and thought, language and power and the idiosyncrasies of human language in relation to knowledge. You will explore knowledge questions related to the four main elements (i.e. scope, perspectives, methods & tools, and ethics) and make connections to the core theme. Remember that the themes are primarily assessed through the TOK exhibition. Nevertheless, you may also wish to explore the connection between language and knowledge in your answer to the prescribed essay title (if relevant), as such reflections could be part of an analysis of the methodology used within a particular area of knowledge.

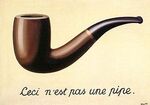

Warm-up reflection: So why is "La Trahison des Images" (Magritte's "Ceci n'est pas une pipe" painting) such brilliant TOK material?

Through his iconic art, painter Magritte lets us explore the relationship between representation and reality. We can indeed use language and symbols to 'map' reality. Within our language, we use words as 'signifiers' to denote something else ('the signified'). But, all too often we blend the signifier with the signified. According to Charles Sanders Peirce, we end up thinking through these signs and we forget what is really out there. Baudrillard takes this notion even further with his conception of 'the hyperreal'. Maps and signifiers (in the broad sense of the word) can be useful as conceptual, organisational, and practical tools. However, when you think through signs, accuracy can give way to simplification. When we blend the signifier and signified, we can also get a distorted understanding of what is really out there.

|

|

Introduction

Language is a medium through which we pass on most knowledge. You could ask yourself how much you would know if you had no language to gather or express knowledge. Our daily language is heavily influenced by the discourse of the most dominant groups in our communities, even though we may not always be aware of this fact. The language we speak can be used to pass on knowledge and values that exist within our community, but it also influences to some extent how we know.

Even though the limitations of the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis's linguistic determinism have been pointed out, new research (eg by Boroditsky, see below on this page, under the section "lost in translation") reveals how the language we speak may shape the way we think. Some speakers of Aboriginal languages have excellent orientation skills due to their linguistic use of absolute cardinal directions, for example. The Japanese legal system seems to be structured differently from the Anglo-Saxon system, which reflects the linguistic differences between the respective languages' causality structures.

|

|

The connection between language, thought and knowledge is so profound that it also leads to a connection between language and power. This leads to a connection with another optional theme: Language and Politics. Through language you can influence and shape thought. You may subconsciously alter the way people speak and think. The political power of language is apparent in propaganda, linguistic stereotyping and through verbal nuances such as euphemisms versus pejorative language employed by politicians. Interestingly, you may not always be aware of the extent to which your knowledge and identity have been shaped through language. Your discourse may oppress people from different communities or advocate certain ideas.

Language and Thought

We use language to make sense of the world and to pass on knowledge. In a sense, language can be seen as a (metaphorical) map we use to represent what is really out there, regarding the natural world as such, as well as more abstract ideas. When we speak, for example, we utter sounds that form words and sentences. These words generally refer to something else. For example, you can utter the sound "cat" to refer to a four legged furry animal. The word "cat" is the "signifier", the actual animal itself, is the "signified". The way in which we use language to refer to something else is called the "denotational" quality of language. When we use language, we often have a generalised, simplified or personalised idea in mind. When you have a pet cat, you are probably thinking of your particular cat, when you say the word "cat". Likewise, when you say "tree", or "breakfast" or "school", you will most likely think of concepts that you have some sort of personal experience with. A breakfast in your part of the world could, however, be very different from what people eat elsewhere. This illustrates that the words we use may mean different things for different people. In addition to these denotational differences (what language refers to), language can have different connotations. These connotations are additional ideas and associations on top of the literal meaning. We sometimes have the choice between several words to refer to the same thing. Each word will express a different type of nuance or connotation. The particular word you choose to talk about something may influence the connotations that surround the meaning of what you refer to. In that sense, language is not neutral. For example, if you want to soften the "negative" or "informal" connotations surrounding the word "to pee", you can use an euphemistic (softer sounding) expression such as "to go to the bathroom," or "to powder your nose". For topics that are taboo (such as "sex", "death", "bodily functions"), we often use such euphemistic expressions. We can also manipulate how people think about important issues by playing with connotational language. If you want to play down the associations of violence associated with war, you can use expressions such as "collateral damage" instead of "bombing a village", "ethnic cleansing" instead of "genocide", or "inoperative combat personnel" for "dead soldiers". To influence opinion surrounding abortion laws, you can use an expression such as "pro life" or "pro choice". Either expression has clear emotional connotations (as well as intrinsic false dilemma), although they essentially refer to the same thing. We can use pejorative (very negative) language to talk about people and things we don't like. We can use sexist and racist language to reinforce stereotypes.

So why does this matter in TOK? If we rely so heavily on language to convey ideas and pass on knowledge, it is important to be aware of the fact that the connection between language and thought is less straightforward than may appear at first sight.

Language is an incredibly important tool to pass on knowledge and to communicate thought. We gather a very large amount of knowledge through language. For example, to acquire knowledge we read information online, research findings of others, look through textbooks, or simply listen to others (like your teachers, for example). We use language to represent ideas, to make sense of the world, and to talk about what is "out there". Nevertheless, the language you speak is closely connected to your world experience. If you speak several languages, you may notice that some languages have words that don't exist in others. This may be because some ideas are more important in some cultures than others. Perhaps your environment and your way of life require a certain type of language and certain expressions. Anthropologist Wade Davis, for example, suggests that the Barasana people tend not to distinguish blue from green because, to them, blue and green together form the colour of "the canopy of the heavens"; an idea closely linked to their world experience. However, it is also worth considering how the actual language you speak may shape your experience of the world (and in its turn, the way in which you gather knowledge). For example, through your study of a second language at IBDP, you might have noticed that some languages have gender, whilst others do not. You may also have noticed that some languages force you to think carefully about which word to choose to address someone else (eg the French vous versus tu). If a language forces you to think about this kind of stuff, does that mean its speakers will "know" (the world) differently? Cognitive scientist Lera Boroditsky claims that the latter is partly the case. She shows in her TED talk and in her article 'Lost in Translation' that Russian people tend to distinguish the shades of blue better because they have an extra word for light blue. In addition, psychologist Elizabeth Loftus claims that our memory of sense perception is also affected by language. In short, the connection between language and cognition seems to be more profound than what was suggested until fairly recently, and the language you speak may shape your cognition.

Although the language you speak will not necessarily determine what you can think, it is obvious that language and thought are interconnected. You can probably think of several examples from your own life where people have tried to manipulate your thoughts through language. This is especially the case when people use emotive and persuasive language. In this respect, language can lead to power. You can use language to shape other people's thoughts and to maintain certain relationships of authority, The connection between knowledge, language and power can be explored further within TOK classes.

So why does this matter in TOK? If we rely so heavily on language to convey ideas and pass on knowledge, it is important to be aware of the fact that the connection between language and thought is less straightforward than may appear at first sight.

Language is an incredibly important tool to pass on knowledge and to communicate thought. We gather a very large amount of knowledge through language. For example, to acquire knowledge we read information online, research findings of others, look through textbooks, or simply listen to others (like your teachers, for example). We use language to represent ideas, to make sense of the world, and to talk about what is "out there". Nevertheless, the language you speak is closely connected to your world experience. If you speak several languages, you may notice that some languages have words that don't exist in others. This may be because some ideas are more important in some cultures than others. Perhaps your environment and your way of life require a certain type of language and certain expressions. Anthropologist Wade Davis, for example, suggests that the Barasana people tend not to distinguish blue from green because, to them, blue and green together form the colour of "the canopy of the heavens"; an idea closely linked to their world experience. However, it is also worth considering how the actual language you speak may shape your experience of the world (and in its turn, the way in which you gather knowledge). For example, through your study of a second language at IBDP, you might have noticed that some languages have gender, whilst others do not. You may also have noticed that some languages force you to think carefully about which word to choose to address someone else (eg the French vous versus tu). If a language forces you to think about this kind of stuff, does that mean its speakers will "know" (the world) differently? Cognitive scientist Lera Boroditsky claims that the latter is partly the case. She shows in her TED talk and in her article 'Lost in Translation' that Russian people tend to distinguish the shades of blue better because they have an extra word for light blue. In addition, psychologist Elizabeth Loftus claims that our memory of sense perception is also affected by language. In short, the connection between language and cognition seems to be more profound than what was suggested until fairly recently, and the language you speak may shape your cognition.

Although the language you speak will not necessarily determine what you can think, it is obvious that language and thought are interconnected. You can probably think of several examples from your own life where people have tried to manipulate your thoughts through language. This is especially the case when people use emotive and persuasive language. In this respect, language can lead to power. You can use language to shape other people's thoughts and to maintain certain relationships of authority, The connection between knowledge, language and power can be explored further within TOK classes.

A glossary of TOK vocabulary related to knowledge and language:

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

|

| ||||||||||||

|

Metaphors illustrate the connection between language and thought very well

|

Acknowledgement: this PowerPoint by Jennifer Kemp has been published with the permission of the author.

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

| ____________how_metaphors_rule_your_life__1_.pptx | |

| File Size: | 2787 kb |

| File Type: | pptx |

|

|

Lost in Translation

What gets lost in translationbetween one language and another?

This lesson focuses on languages in translation. It emphasises how speakers of different languages "know differently" when speaking (and thinking) in their language. This lesson offers a good opportunity to explore how TOK manifests itself in the real world. Bilingual students, as well as group 2 learners, are often able to draw from their own experiences. Research in the field of cognitive science may further support knowledge claims in this area. In addition, the study of novels in translation (language A) can be discussed within this context.

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Language and Power

Politicians and advertisers are very much aware of the power of language. A clever use of language may influence what people will accept as true knowledge. The connection between language, knowledge and (the abuse of) power provides excellent material for TOK discussions. Language can reinforce relationships of authority, oppress marginalised groups and manipulate thoughts of less knowledgeable people. Political propaganda, euphemistic language, and the censorship of expression(s) demonstrate the connection between language and power. The history of mankind is thronged with examples of cultural imperialism through language. Which dialect of your mother tongue do you associate with wealth and education? Why is that? Are we, albeit subconsciously, using language to reinforce social class, gender boundaries and ethnic hierarchies?

The brilliant book 1984, by George Orwell, really makes us think about the relationship between language, thought and power. 1984 is a dystopian novel which imaginatively explores the possibilities of a totalitarian society in which free choice and individual thought are controlled by the state ['big brother is watching you']. The novel explicitly discusses the power of language as a tool to gather, limit or control knowledge. The following quote from the novel illustrates this point:

“Don't you see that the whole aim of Newspeak is to narrow the range of thought? In the end we shall make thought-crime literally impossible, because there will be no words in which to express it. Every concept that can ever be needed will be expressed by exactly one word, with its meaning rigidly defined and all its subsidiary meanings rubbed out and forgotten. . . . The process will still be continuing long after you and I are dead. Every year fewer and fewer words, and the range of consciousness always a little smaller. Even now, of course, there's no reason or excuse for committing thought-crime. It's merely a question of self-discipline, reality-control. But in the end there won't be any need even for that. . . . Has it ever occurred to you, Winston, that by the year 2050, at the very latest, not a single human being will be alive who could understand such a conversation as we are having now?”

The brilliant book 1984, by George Orwell, really makes us think about the relationship between language, thought and power. 1984 is a dystopian novel which imaginatively explores the possibilities of a totalitarian society in which free choice and individual thought are controlled by the state ['big brother is watching you']. The novel explicitly discusses the power of language as a tool to gather, limit or control knowledge. The following quote from the novel illustrates this point:

“Don't you see that the whole aim of Newspeak is to narrow the range of thought? In the end we shall make thought-crime literally impossible, because there will be no words in which to express it. Every concept that can ever be needed will be expressed by exactly one word, with its meaning rigidly defined and all its subsidiary meanings rubbed out and forgotten. . . . The process will still be continuing long after you and I are dead. Every year fewer and fewer words, and the range of consciousness always a little smaller. Even now, of course, there's no reason or excuse for committing thought-crime. It's merely a question of self-discipline, reality-control. But in the end there won't be any need even for that. . . . Has it ever occurred to you, Winston, that by the year 2050, at the very latest, not a single human being will be alive who could understand such a conversation as we are having now?”

Human, de-humanised and artificial languages.

A language for each occasion

Language is far from neutral and the knowledge passed on through language may consequently lack objectivity. People have long been aware of this fact. Depending on the area in which you are constructing knowledge, you may or may not want to remove "the human fluff" from language. You will notice that the language you use in the Natural Sciences, for example, is generally more "neutral" and "free of imagery" than, let's say the language you use to analyse a poem in English Literature or an image rich painting in the Arts. In Mathematics, we have even attempted to create a unique and universal language that is almost complete void of human subjectivity. The richness of human language can be a blessing in some circumstances, but a hindrance to knowledge in others.

Removing human fluff

With the advent of "machine language" and technological advancements, we have ventured into a whole new territory. How useful is it to remove human qualities from a language? Does this lead to more reliable knowledge? Converting ideas into codes has created endless opportunities for new knowledge. But is this perhaps reductionist? Machines are now able to learn and translation devices are becoming smarter, but there is something about human language which machines find hard to get right.

Language, knowledge and complex ideas

One of the things that makes humans unique is our ability to use language to express complex ideas. True, animals have their own version of language (sometimes these abilities are quite impressive, like is the case for Bonobos, for example). However, Can animals truly know, given their fairly limited means of communication? How much can we know without language? How important is (human) language for the acquisition of knowledge?

|

|

What artificial languages can teach us about the nature of language.

The language of Dothraki (Game of Thrones) has been taught at a US university. Linguist David Peterson, taught students about the language he created for the famous series as well as the art of language invention as such. Although languages normally develop organically over time, several artificial languages have been created throughout human history, with Esperanto perhaps being the most famous of them all. The creation of new languages, as well as the dying out living languages, give rise to some very interesting questions about what we need or want from a language. What do we want to express and how? What can or can't be translated? What happens if life moves on but a language doesn't? When you study a dead language, such as Latin, you will be able to translate what is written on paper, but do you really get what it means? After all, your life is so much different from the Romans'. Likewise, in Latin you won't be able to fully express feelings and concepts that are from the modern world without being creative and adapting the dead language. How would you say "I updated my homepage", in Latin, for example? Language and thought are interconnected, which is why the topic is so interesting to analyse in TOK. In the interview below, Peterson discusses some of the challenges he faced in his language creation. Apart from the practical issues such as linguistic consistency and phonological representation, artificial language creators have to overcome the bias towards their own language(s) and discourse to imaginatively conceive what other people(s) may want to express and how.

| nature_of_language.pptx | |

| File Size: | 4930 kb |

| File Type: | pptx |

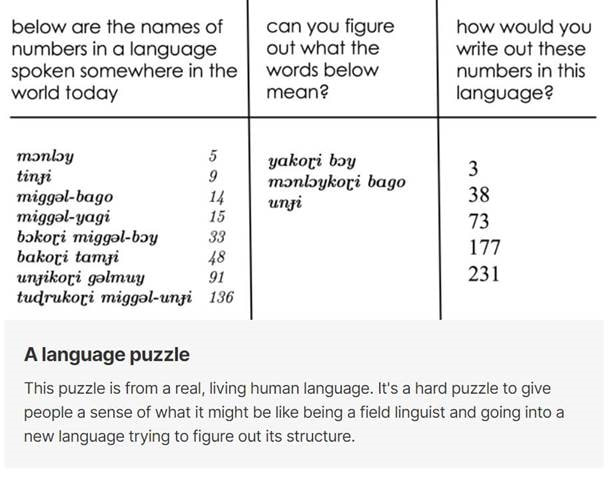

Lesson idea: Creating a new language for an imaginary people.

On Language,Thought, and Culture.

You have been tasked with the creation of a new language for an imaginary people of the next blockbuster series or film, just like Peterson (see video below) had to create "Dothraki" for Game of Thrones. In groups, consider the following:

|

|

|

Unit plan on knowledge and language

A series of lessons exploring how we use language to map what we know, the connection between language and culture, and the link between language and power.

The unit plan:

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

| language_unit_and_lesson_plan.docx | |

| File Size: | 738 kb |

| File Type: | docx |

Presentations, handouts, and other resources per lesson:

|

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

|

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

|

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Possible knowledge questions on knowledge and language

Acknowledgement: these knowledge questions are taken from the official TOK Guide (2022 Specification)

|

Scope

Ethics

|

Perspectives

Methods and tools

|

Making connections with the core theme, as suggested by the TOK Guide.

- Is it the case that if we cannot express something, we don’t know it

- How does language allow us to pool resources and share knowledge?

- Do people from different linguistic or cultural backgrounds live, in some sense, in different worlds?